On the morning of May 10, 1946, nearly a hundred reporters, scientists, and military officials gathered in the remote New Mexican desert to witness history. A thousand yards across the sand, in a cleared basin, stood a German designed V-2 rocket, readying for its journey into space. While there were no explosives on the rocket, there was plenty of propellent; spectators were instructed to throw themselves flat on the ground in the event of an explosion on take-off. The impending launch would be the first of 25 such rocket tests at White Sands Proving Ground over the coming months.

A button was pressed, activating the ignition apparatus that started the rocket fuel working. After ten seconds, enough energy was generated for lift-off. The rocket slowly rose, gaining speed as it climbed, eventually reaching a top speed of 3200 miles per hour. The rocket could travel up to 230 miles but would be brought down in the desert not far from where it launched. The people of El Paso and Juárez, just under 50 miles to the south, need not worry, the rocket was pointed north and, instead of a warhead, the rocket was equipped with a “peacehead” full of scientific instruments designed to send back data.

Launches continued every other week for the next year. The following May, a new, experimental rocket, codenamed Missile 0, would make history.

And all this science, I don’t understand...

Selected for its isolation and vast stretches of white gypsum dunes, White Sands had been home to secret military tests since World War II. In July 1945, one such test could be seen and felt as far off as El Paso, where it was reported in the papers as a massive ammunition explosion. Weeks later, two similar explosions would end the war and the results of the Trinity Test would be known to the world.

At the end of the war, as part of Operation Paperclip, the United States snatched up as many German scientists and their rockets as they could before the Soviets could get to them. More than one-hundred Germans were brought to Fort Bliss to begin work on the nascent American rocket program. Among them was Wernher von Braun, the controversial scientist who held the distinction of being perhaps the only person to have worked for both Adolf Hitler and Walt Disney.

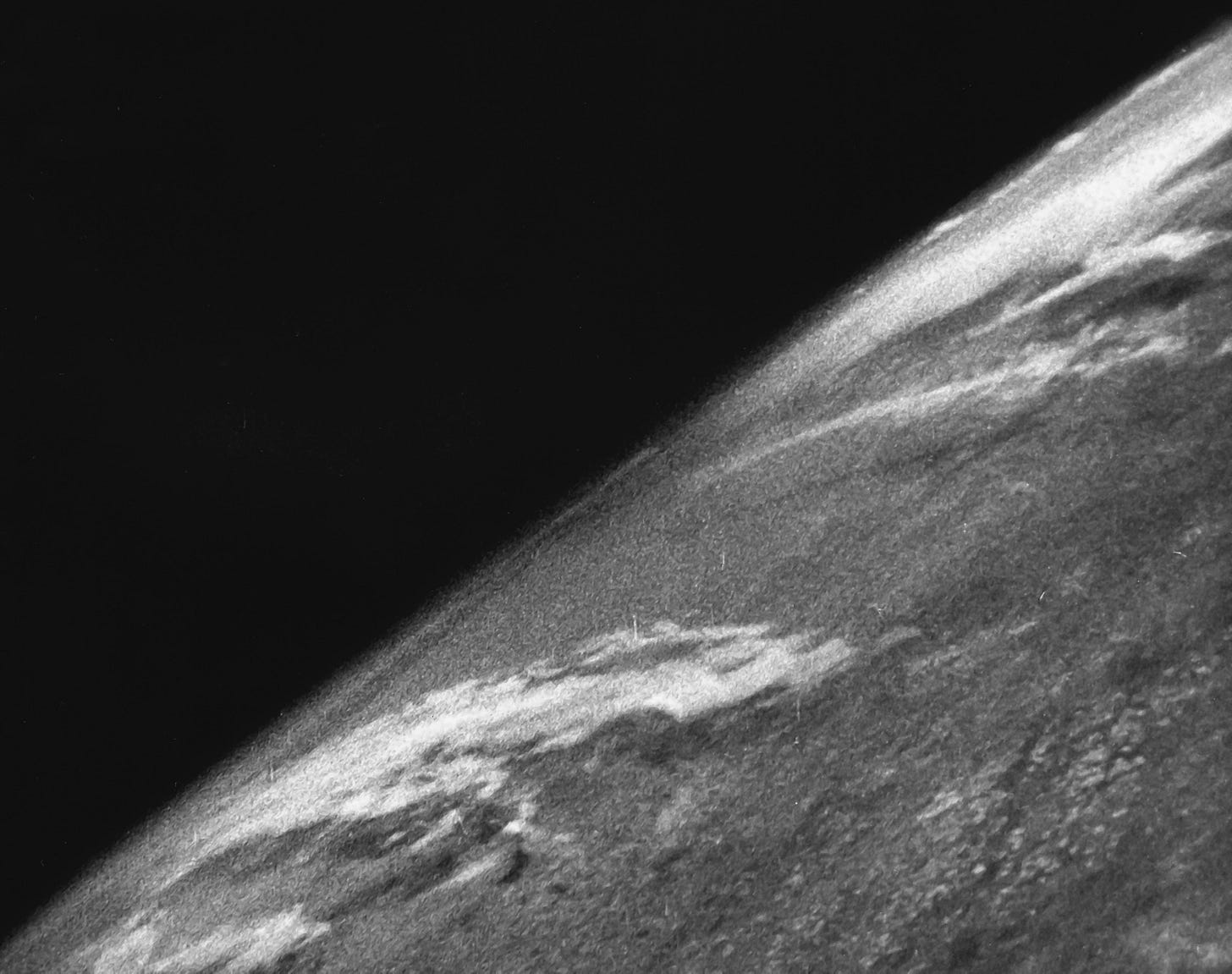

The unsavory elements of the Germans’ recent past could be overlooked for the benefit of national security and science. The V-2 rocket, or Vergeltungswaffe-2, German for “vengeance weapon” 2, was the first artificial object to reach space; it and its designers were of untold value to whoever controlled them. The newspaper referred to them as “Nazi Rockets”, an unfair label as the rockets held no political ideology of their own.

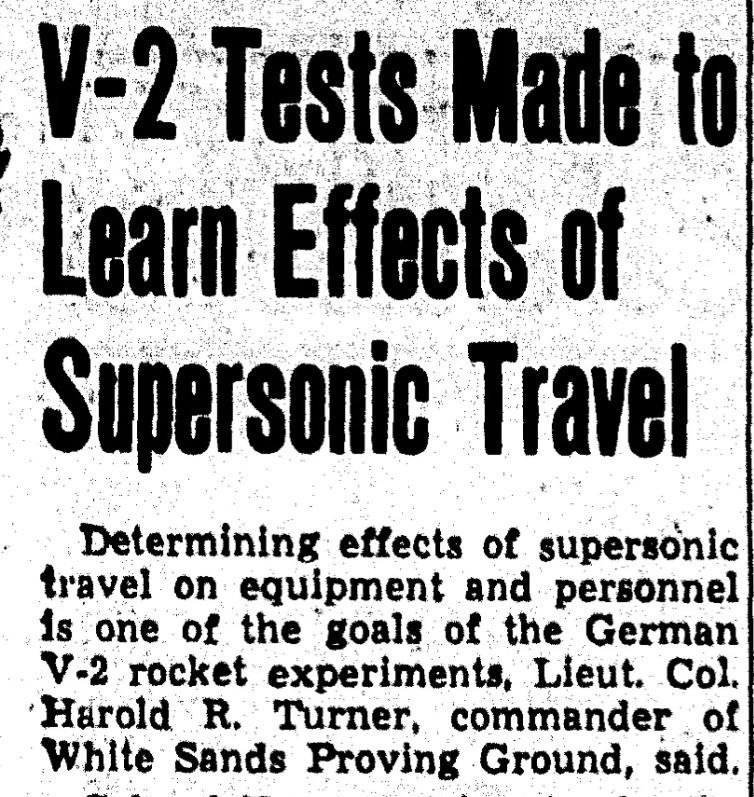

These apolitical rockets promised an improved standard of living for all through advances like US Mail by rocket. Someday humans might even travel by rocket, though not on V-2, which the scientists conceded would be a lethal trip. Nonetheless, the V-2 allowed for bleeding edge research into supersonic travel.

Mars ain't the kind of place to raise your kids…

Welcoming our former adversaries into the country created some unease. Questions were raised as to whether the scientists, including former Nazis, had escaped justice. The Federation of American Scientists demanded the Germans be denied work in the private sector and be returned to Germany as soon as possible. When their treatment drew scrutiny, the Army made it clear the scientists were not being “feted as heroes.”

“The scientists are not prisoners of war,” said Brigadier General H. B. Saylor, chief of Research and Development, Ordnance Development. “We have limited their activities, and there is a censorship in effect. But the Army is not entertaining and ‘feting’ them.”

While the Germans were paid and afforded some freedom to move around the El Paso area, they were kept in bunk houses on base and considered to be in military custody. If their work and conduct was deemed satisfactory they would be allowed to apply for US citizenship. Eventually, their wives were allowed to settle with them. They were enrolled into classes, at the husbands’ expense, to learn English and understand American customs. Their children were allowed to attend El Paso schools, paid for by the parents. They were not allowed to use the swimming pool on the base.

Burning out his fuse up here alone...

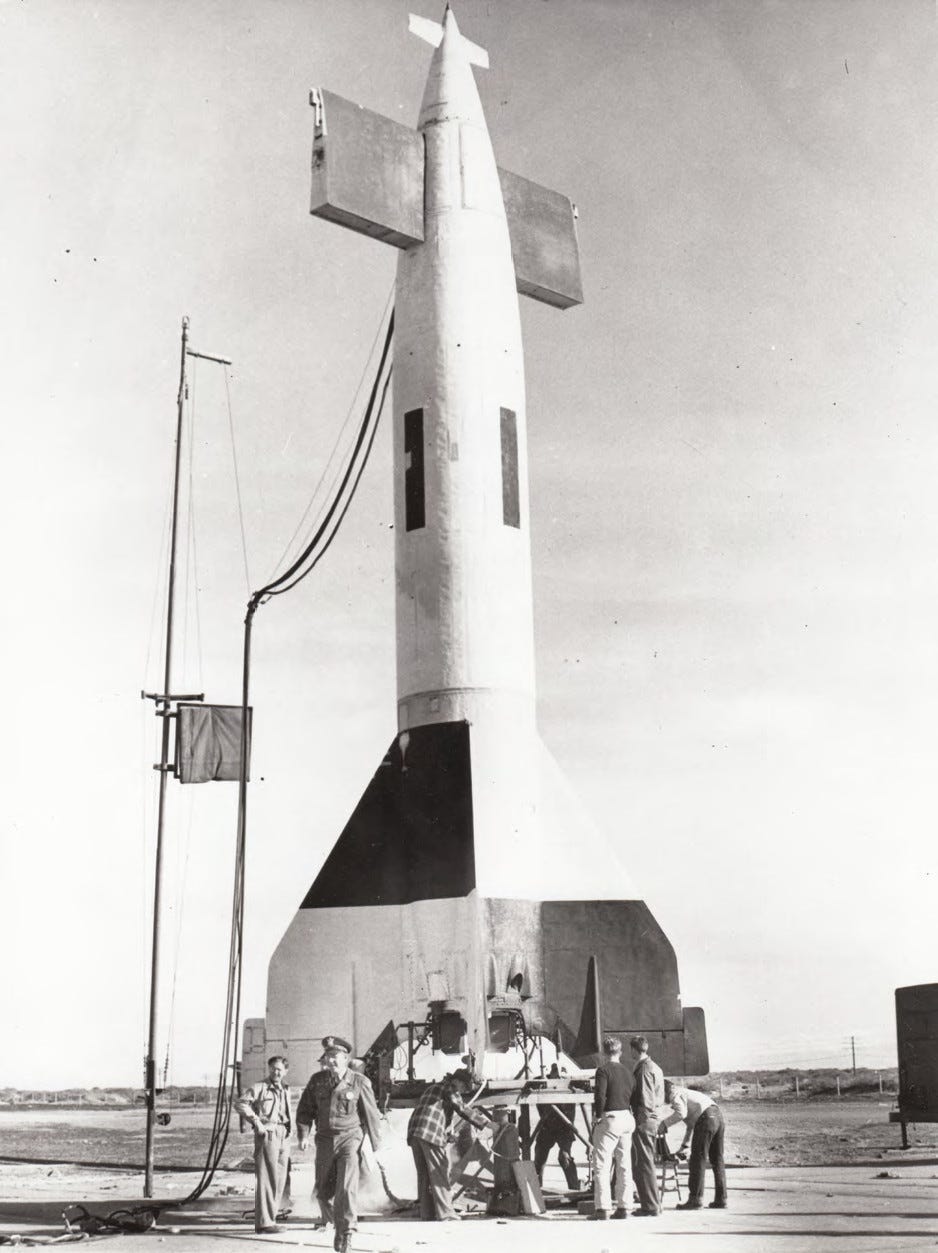

After two dozen or so V-2 launches, it was time for something new. The Hermes II was a modified V-2, a first of its kind two-stage, ramjet vehicle fitted with a prototype guidance system. The rocket had an unusual design, its ramjets - air breathing jet engines - stuck out from the sides as large wings near the nose. These wings required the tail fins to be enlarged, making the rocket unstable without the advanced guidance system.

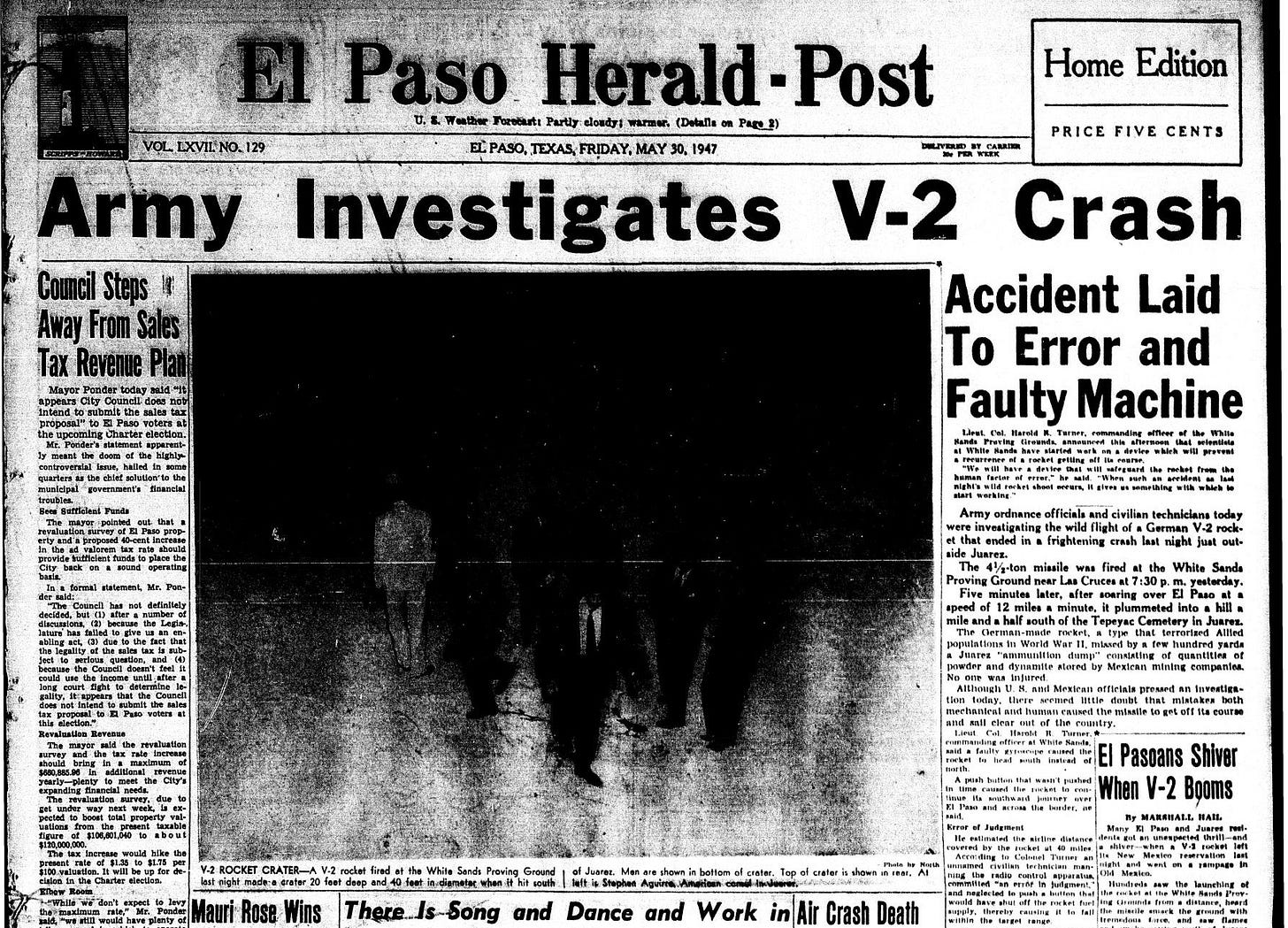

On the evening of May 29, 1947, the Hermes II set out to make history, one way or another. At 7:30 p.m. the rocket, codename Missile 0, launched into the sky. It was programmed to fly up-range to the north, at a seven degree vertical angle, but it drifted south. At first, it was only slightly off course and mission control thought it would stay within the proving ground, or at least within Fort Bliss. Sadly, this was not the case and the rocket made an aggressive move south, on a direct course for El Paso. Exactly what happened next remains in dispute. What is not in dispute is the rocket veered off course and crashed into a rocky hill near Tepeyac Cemetery in Juárez, just three miles south of the city’s business district.

The force of the crash shook buildings and shattered windows across Juárez and El Paso. The neon lights in downtown El Paso flickered off and on. A clock in the El Paso Sheriff’s office stopped at the time of the impact, 7:32 p.m. All that remained of the rocket was a few scraps of red hot metal scattered around a perfectly rounded crater, about 50 feet in diameter and 24 feet deep. The rocket landed just yards away from a mining company’s dynamite storage. Miraculously, nobody was hurt.

It was a bad day for aviation overall. In addition to the rocket explosion, four separate plane crash stories appeared on the front page of the El Paso Times.

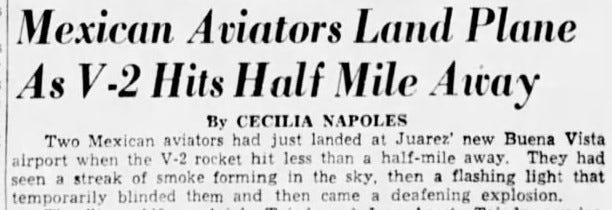

The only aviators to make the front page for a successful landing were cousins Alfonso Ariola Tejada and Jose Acosta Tejada. The Tejada cousins had just landed at Juárez’s Buena Vista airport when the rocket hit less than a half-mile away. The aviators saw a streak of smoke followed by a flashing light that blinded them momentarily, then came the deafening explosion. The cousins rushed to the scene and were among the first to arrive.

A mere six-hundred yards away, Narcisco Vargas, Tepeyac cemetery’s caretaker, had an up close view of the crash.

“Suddenly there was a terrible noise,” Vargas said, “accompanied by a ball of fire which seemed to engulf me. I must have bounced into the air because the next thing I knew I was lying face down on the ground. There was a black cloud of smoke and dust all around us and I almost choked. I could hardly breathe. It seemed like a tornado. Dishes were broken in my house and a table was overturned.”

The Washington Daily News called it “the night hell exploded” in Juárez. “Natives living in the wild,” as the paper put it, “dropped to their knees in prayer as the rocket exploded. The blast blew out a candle in a native hut a quarter of a mile from where the missile struck.”

In El Paso, witnesses reported seeing the vapor trail of the rocket and an explosion said to look like a miniature atomic bomb. Shockwaves were felt and flames could be seen as far out as Fabens and Anthony. Many assumed it was a refinery or other industrial explosion across the border. An early radio report out of Juárez said it was a train car explosion.

The event threatened a mass panic, touching the lives of thousands along the border. Louis, a man of 23, was fighting with his girlfriend when the explosion sent her leaping into his arms. Thanks to the rocket, the couple made up.

In other parts of the city, life went on, unmoved by the chaos. The explosion was not enough to break up the Spring Fiesta being held at the International Museum. Some thought the blast was just part of the event.

Mexican officials were surprisingly low key about the incident. When Maj. Gen. John L. Homer, the commander of Fort Bliss, apologized to his Mexican counterpart in Juárez, the Mexican General brushed the accident off as “one of those mistakes” that happen in the military.

The accident was attributed to a combination of faulty equipment and human error. The mechanical failure was a gyroscope that might have been wired backwards, sending the rocket south instead of north. The German made gyroscope was described by an official as “ancient.”

The human error, according to Lt. Col. Harold R. Turner, commanding officer at White Sands, was a push button that wasn’t pushed in time, allowing the rocket to continue its southward journey into Mexico. Why the button wasn’t pressed in time, and whose responsibility it was to push the button, remains in dispute. White Sands officials disclosed that German scientists had taken part in the launch and that it was a civilian technician blamed for the mistake, but the identity of the so-called “Button Bungler” was not revealed.

Differing versions of what happened that evening in the control room have emerged over the years. In one telling, a project scientist physically restrained the Range Safety Officer from pressing the button, believing the test vehicle’s propellant load should not be wasted just for safety’s sake. The rocket was estimated to have 300 gallons of fuel left when it fell.

In a more heroic version of events, the flight crew chose not to shut down the missile for fear that it might still have enough momentum to crash into El Paso. By letting it operate longer, it overflew most of the El Paso/Juárez area. Whatever the case was, more strenuous precautions would be taken in future launches.

El Pasoans took the close call in stride and support remained for continuing the tests. The editor of the El Paso Herald-Post was confident the “proper authorities” would take steps to prevent a repeat incident.

“Experimental work such as that being done at White Sands must go on, with precautions necessary for the protection of lives,” the paper declared.

V-2 launches continued into the early 1950s. Eventually, the original German equipment ran out and the missions came to an end. The U.S. Air Force and later NASA were born and the focus shifted to space exploration and ICBM development. Production of long-range capabilities spread out to Alabama and Florida. The space program moved on and White Sands remained focused on missile and air defense systems.

Wernher von Braun and most of the other Germans followed the space program elsewhere. One of the Germans, Kurt Debus, went on to serve for years as the Director of the Kennedy Space Center. When Debus retired in 1974, von Braun roasted him on his humble beginnings in New Mexico.

“Kurt’s first debut in this country was not so successful as some of his later efforts. He almost hit a house of ill-repute in Juárez, Mexico, with his first launch from White Sands Proving Ground.”

![Or Give Me Death Industries [substack edition]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!rF5C!,w_80,h_80,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep,g_auto/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F6790ca65-d171-497c-85d0-70c43dab81be_736x736.png)

![Or Give Me Death Industries [substack edition]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!C8FR!,e_trim:10:white/e_trim:10:transparent/h_72,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F918e6633-25ca-4b95-b28f-d4d1bfeccce8_1344x256.png)

![Or Give Me Death Industries [substack edition]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!rF5C!,w_36,h_36,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep,g_auto/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F6790ca65-d171-497c-85d0-70c43dab81be_736x736.png)

Another amazing article!