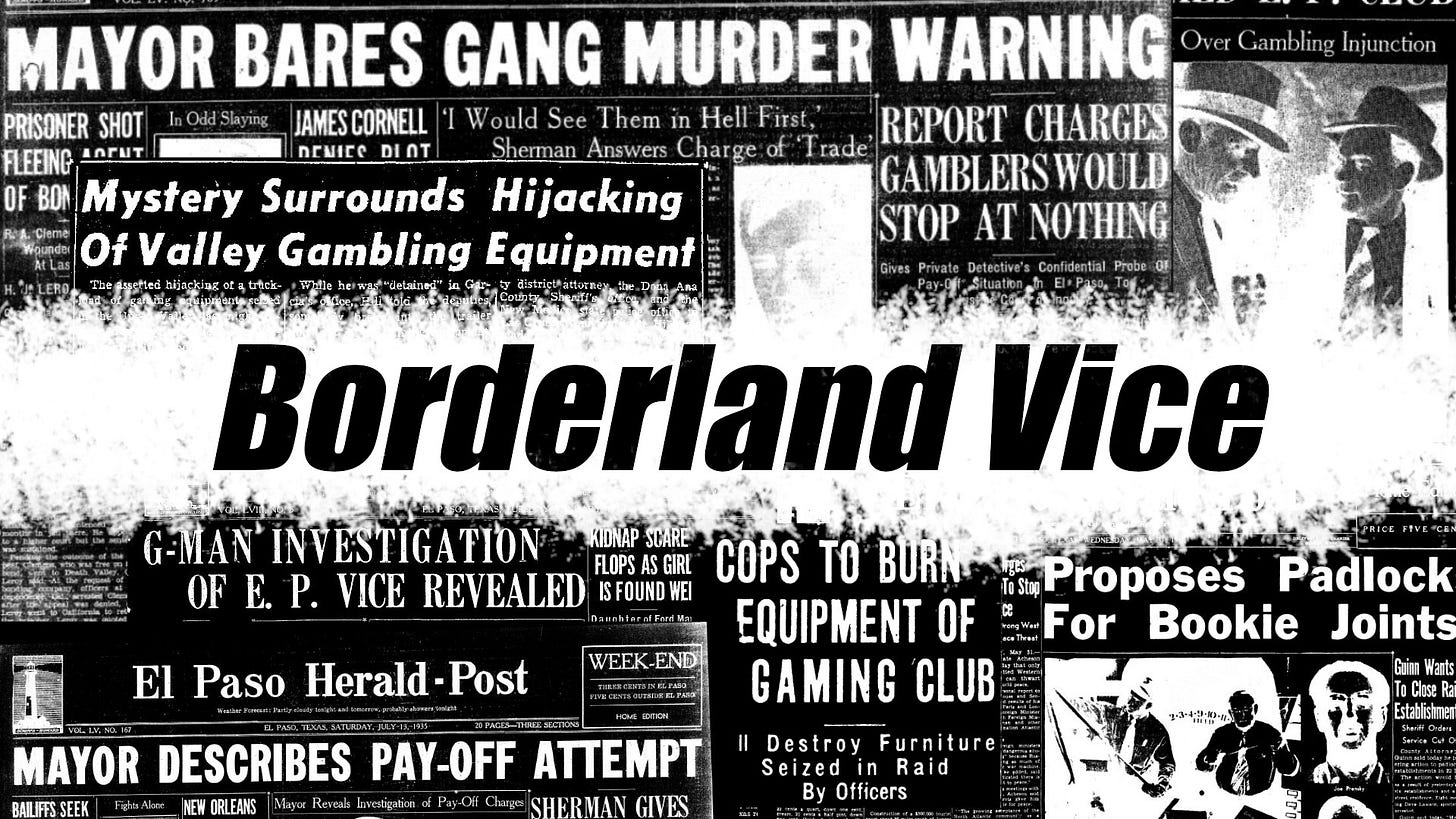

Borderland Vice

Part 1: The Book of Loeb

Part 1 in a three-part series on the last gasp of open gambling in the Borderland. [Read Part 2 & Part 3]

“A gambler is a funny proposition,” said the thin, gray man between drags off a hand rolled Bull Durham cigarette, “he knows he’s an outcast.” Aged 72 and in failing health, the man’s cheeks were sunken, and he struggled to breathe, sucking through his lips at every few words. Despite his frail state, he countered the reporters’ questions with ease. “El Paso gamblers are not smart, but I tell them they are.”

El Paso newsmen had gathered in the modest living room of the city’s purported “dictator” of gambling so that he might clear the air surrounding his recent grand jury testimony. One reporter asked for a photograph. “No!” shouted a woman from the adjoining room.

“I guess that settles it,” the man wheezed through a smile. “I’ve never been in a court suit, and never saw the inside of a grand jury room until Thursday,” he bragged.

Leo J. Loeb had worked his way up from bellboy to a political powerhouse of El Paso. The press labeled him the “boss fixer” of El Paso gamblers, a title he rejected. “There is no political boss at present. I am not one,” he assured reporters. Nonetheless, he maintained a little black book of campaign expenses, none of which came from gamblers, of course.

El Paso had been a gambling mecca since the arrival of the railroad in 1881. By the dawn of the 20th century, the city was known as the “Monte Carlo of the United States.” Despite a formal ban on open gambling in 1905, the games held on for another generation. But the Great Depression tightened cash and a new wave of reformers sought to stamp out the practice once and for all. Leo Loeb and his era were coming to an end.

This is the story of the last gasp of open gambling in the Borderland. It’s a story of rivalries, corruption, crusading reverends, phony detectives, and even murder. It crosses all strata of society, from desperate gamblers on their last penny ante to the city’s major players with names recognizable today. Ultimately, it is the story of El Paso shaking off the last vestiges of the Wild West.

The Boss Fixer

Gambling operated as a well-organized machine for years in El Paso. Police crackdowns were rare, with only the occasional raid put on for show “to satisfy the church element.” Raids seldom resulted in prosecution beyond minimal civil fines. Lack of evidence was typically cited to brush away more serious charges.

The ease of gambling operations required steep political payoffs as a cost of doing business, yet profits remained high. Then came the Great Depression and with it a contraction in the sucker market. A handful of well-resourced gamblers began to squeeze out the competition and Leo Loeb emerged as the new boss fixer, the primary organizer of gambling in El Paso.

Loeb was born December 22, 1863, in Memphis, Tennessee. His father was a Confederate soldier and his mother a suspected spy. Accused of sheltering Confederates from the Union, the family fled, ultimately settling in Little Rock, Arkansas where Loeb was raised. Loeb worked as a bellboy, rising to hotel manager before becoming a professional athlete. He moved to England where he was a “money runner”, running in foot races bet on like the horse races. His next move was starting a wire service.

“That was my only real connection with gambling - if you want to call it that,” Loeb told reporters. “We furnished the news on horse races, baseball games, football games - even a yacht race or two. I had a central switchboard. If our customers paid every week, they were plugged in. If they didn’t pay, out came the plug until they did.”

After dabbling in everything from diamond and pearl buying to real estate, Loeb found his way to El Paso in the 1920s. He quickly became a major player in the gambling community and beyond. “I have friends in every walk of life,” Loeb said. “I know most of the gamblers in town – better than they know themselves. I also know church people. My wife is head of a church circle.”

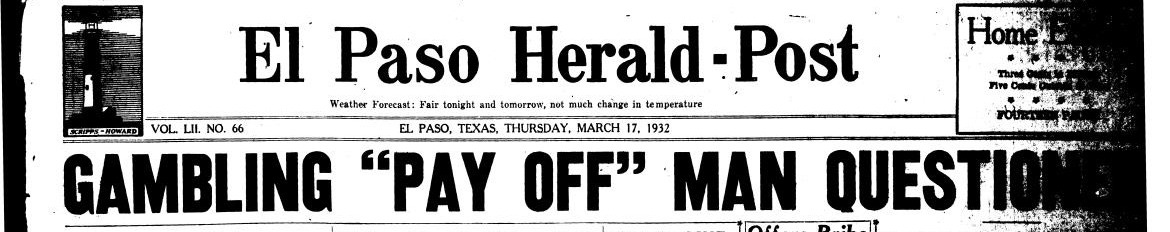

The friends he made in politics did not come cheap. Rival gamblers accused him of running a payoff racket, levying weekly tolls on gaming houses anywhere from $200 to $1200 to distribute as campaign contributions. Any gamblers who didn’t pay up risked having their games raided. Feeling the pinch, several disgruntled gamblers began to talk to the papers. It wasn’t long before the editorial page of the El Paso Herald-Post was banging the drum for an investigation. In the spring of 1932, Loeb found himself before a grand jury.

A Note on Sources

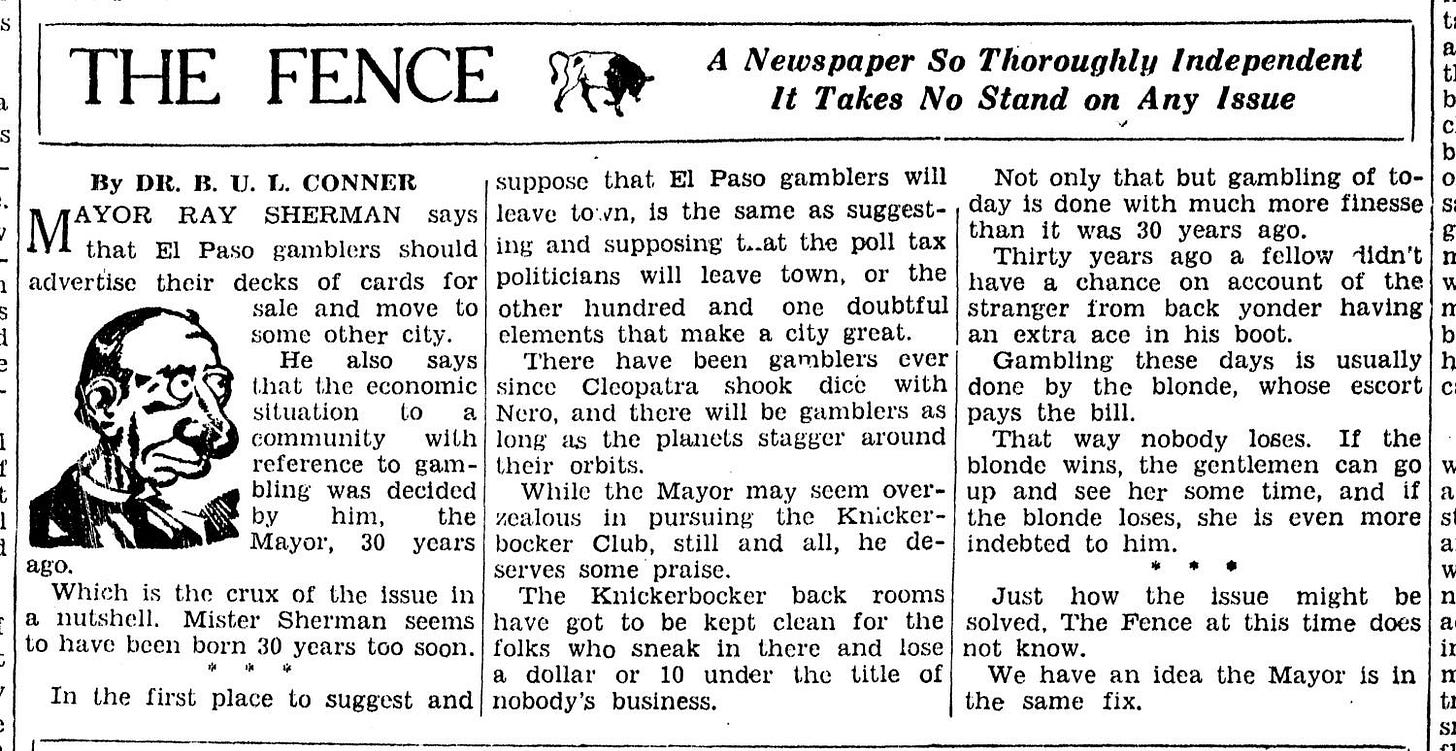

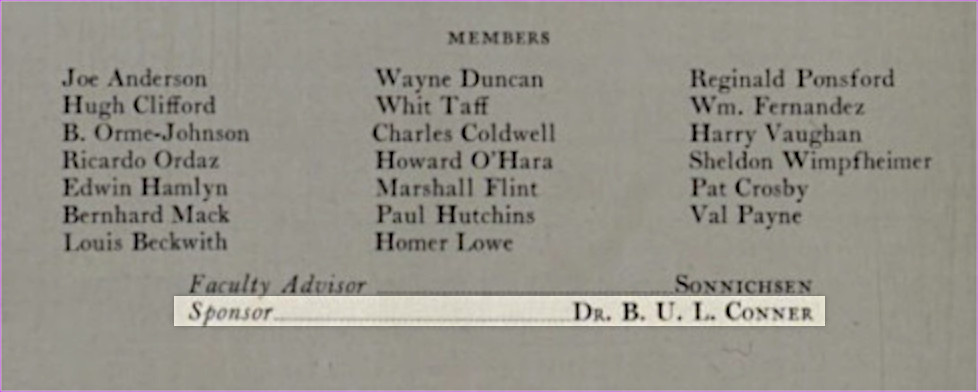

This story relies heavily on reporting from the time, particularly from the El Paso Herald-Post. The Herald-Post pursued the gambling issue vigorously and its editor, Wallace Perry, frequently clashed with politicians, earning him the label of “professional aginner” (as in one who is against something). But one columnist at the Herald-Post stands out: Dr. B. U. L. Conner.

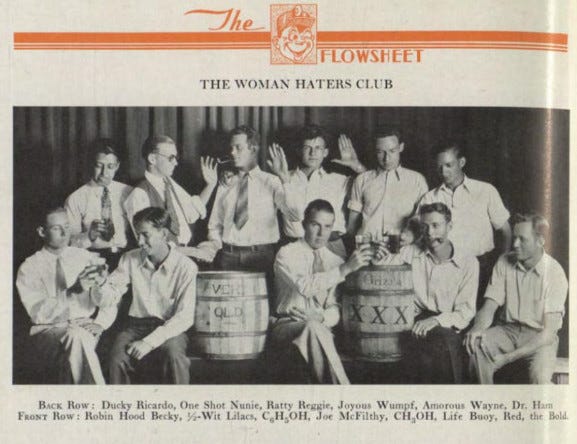

An almost mythical figure, Dr. B. U. L. Conner was the pseudonymous author of the recurring Herald-Post column The Fence, whose motto was “A Newspaper So Thoroughly Independent, It Takes No Stand on Any Issue.” Invented by Birmingham Post columnist and editor Edward Towner Leech in the 1920s, Dr. B. U. L. Conner was syndicated for decades across several Scripps-Howard newspapers, including the Herald-Post. Conner was a household name, so much so that it inspired the nickname of that other villainous person of a similar name. In El Paso, Conner was a pillar of the community, he even served as sponsor to the satirical Texas College of Mines student group, The Woman Haters Club.

Behind the comedic guise of Conner, the Herald-Post offered its not-so-subtle viewpoints on the days’ events, including the gambling saga. The good doctor serves as the Greek chorus in this drama, commenting on events throughout and taking jabs at those involved.

Now back to the story.

The Knickerbocker Club

Loeb denied ever having received gambling money aside from $20 won in friendly card games. He downplayed the label of political boss. “I’d tell [the gamblers]: ‘Now look here. This man ought to be elected.’ I wouldn’t promise them anything,” Loeb said. “I just appealed to them from their own interests.”

While not a gambler himself, Loeb praised those gamblers he saw as the “higher type” who kept their word. He insisted games were always straight at a place he had not personally visited, the Knickerbocker Club.

Located on South El Paso Street, in the shadow of the luxurious Hotel Paso Del Norte, the Knickerbocker Club was ostensibly a bowling alley operated by entrepreneur and World War One veteran, Dave Lawson. In the early 20th century, bowling did not enjoy the family friendly reputation it does today. Bowling then was associated with saloons and gambling, with the bowling often just a front for illicit activities. The Knickerbocker Club was no different and continually flouted the law.

Raids on the Knickerbocker were common, but consequences were not. After one half-hearted raid in the summer of 1931, poker and blackjack tables were seized and destroyed but the club was let off with a $50 civil fine. Felony charges for operating a gambling parlor, which carried penalties of two to four years in prison, were not pursued. Officials explained they only had evidence of one night of gambling; they could not prove gambling had gone on previously or that the club was a gambling house. It was a shaky explanation given previous fines and raids dating back to the 1920s.

Gambling inevitably continued within weeks, including reported incidents during the American Legion convention, held in the fall of 1931. It was well understood that when major conventions came to El Paso there would be gambling for the visitors and police would look the other way. This was especially true for the American Legion.

“Legionnaires can make all the ‘whoopee’ they want to as long as they don’t maliciously destroy property or commit murder,” Police Chief L. T. Robey told the press. Chief Robey said no special effort would be made against gambling during the convention. “I will raid games or gambling places if someone cares to swear out a complaint.”

Predictably, the convention was a boon for the gamblers. The Herald-Post reported card, dice, and even roulette games operated at hotels across downtown and, of course, at the Knickerbocker. Cappers, or recruiters for games – that lucky person who conspicuously wins big at 3-card-monte and entices others to play – were seen fanning out across hotel lobbies in search of suckers.

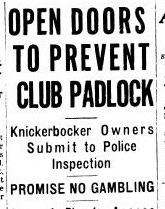

After the convention, the district attorney had seen enough. He sought an injunction to end gambling at the Knickerbocker once and for all. If the DA could prove the Knickerbocker had shown “habitual use” for the “keeping or exhibiting of games prohibited by Texas law,” then the county could padlock the club’s gambling rooms. It seemed like a low threshold to clear, given the club’s history.

Instead, they cut a deal: to avoid a padlock on the club, the owners agreed to submit to police inspections and promised no gambling. Iron barred doors that had been used to lock down the games in the event of a raid were removed. The cops would be allowed in anytime and were free to inspect any room they wished. The court agreed to the proposal, but the judge kept a restraining order in place, warning that future gambling would put club operators in contempt of court.

That was the end of gambling for Dave Lawson and the Knickerbocker Club - for about three months. In March 1932 it was convention time again, this time for the cattlemen, which meant the games were back on.

El Paso Mayor Raymond E. Sherman brushed off concerns, insisting El Paso had no more gambling than any other city of its size. He said gambling was to be expected at a cattlemen’s convention more than others, like say, at a convention of the “Young People’s Christian Endeavor society.”

“That’s why a lot of cattlemen go to conventions - to gamble,” the mayor said. “But, of course, that wouldn’t excuse an officer of who saw gambling going on for not making arrests.”

Nevertheless, Mayor Sherman did take some action, personally ordering the police to obtain an injunction to close gambling at the Knickerbocker. The mayor boasted his pressure was keeping the gamblers on the move, making it harder for would-be customers to find them.

Lax enforcement during the cattleman’s convention sparked outrage. Political payoffs for protection had long been suspected and the latest incident of police looking the other way forced an official investigation. A grand jury was convened, Leo Loeb and the gamblers were summoned for questioning. But, as was typical, evidence was deemed insufficient and no charges were brought. Speculation over packed juries and payoffs persisted.

The games continued and the Knickerbocker remained the hub of El Paso gambling. The Herald-Post named it El Paso’s “wickedest gambling resort.” Raids persisted over the years to the point where members of City Council asked if the mayor’s repeated and seemingly exclusive raids on the Knickerbocker constituted persecution, not prosecution. The Herald-Post was unsympathetic, speculating that the raids were good for business, serving as free advertising for what really went down at the bowling alley.

The Reverend’s Crusade

The crusade against the gamblers came to a head in the spring of 1935. Placated for years, the church element was fed up. Reverend L. O. Vermillion demanded action, threatening to file an injunction suit of his own to shutter gambling halls. The Reverend wrote to Governor James Allred, laying out the facts on the ground but stopping short of demanding the Texas Rangers be sent to El Paso to enforce the law.

Mayor Sherman, a would-be reformer, decided to act. A familiar series of events ensued: the Knickerbocker was raided, arrests were made, but no serious charges were brought. The cases were closed and Dave Lawson was let off after forfeiting a $35 bond. Twisting the knife, the gamblers’ attorney, W. H. Fryer, insinuated the raids were a result of Mayor Sherman not receiving the Knickerbocker’s backing in his last election. “I am sure that when the mayor leaves office it will be without the shadow of suspicion that he ever has received graft from the gamblers,” Fryer said.

Another series of raids on the Knickerbocker and other clubs were ordered later that summer with similar results. Dave Lawson and his fellow gamblers were once again released on a $35 bond. This repeat episode was too much for the mayor and district attorney to bear, especially given rumors of advanced knowledge of the raids. A grand jury was once again convened but once again the grand jury “no-billed” the gamblers, declining to pursue felony charges. Mayor Sherman had to settle for misdemeanor charges against Lawson and his cronies.

“Grand juries, like blondes, are sometimes difficult,” Dr. B. U. L. Conner mused.

Rev. Vermillion was having none of it. In an open letter to the El Paso Times, Vermillion alleged payoffs and packed grand juries were at the heart of the gambling situation. He demanded a real investigation.

County Attorney David Mulcahy relented and requested that Justice of the Peace J. M. Goggin call a court of inquiry to investigate gambling and payoffs. Justice Goggin was livid, accusing Mulcahy of playing politics and putting him on the spot by going to the press with his request. Goggin nonetheless agreed to an inquiry, but blocked the county attorney from participating. “I’ll conduct this investigation myself - they won’t have anything to do with it,” Goggin fumed.

“If digging into this dirty mess of charges and either proving or disproving them is politics, I’m for more politics in public office,” Mulcahy shot back.

This court of inquiry would be the most sensational to date. Extra seats were brought and more than 100 spectators were turned away. Day one did not disappoint. In a stunning move, the court granted immunity to Dave Lawson and the other gamblers with pending charges in exchange for their testimony. Political corruption, not the underlying gambling, would be the court’s focus. The gamblers would be held under rule - isolated under court supervision - until their turn on the stand.

Testimony began with Rev. Vermillion’s revelation that he had been working for Mayor Sherman to probe gambling. Vermillion caused a “mild sensation” when he claimed that Police Chief Robey’s sister-in-law lost $2000 gambling in the Knickerbocker Club, losing $100 to $200 every week. The Reverend said he investigated the rumor himself by visiting a pawn shop where the Chief’s sister-in-law was said to have pawned her jewels to cover her debts.

“I found that she had pawned some of her diamonds and rings,” Vermillion testified. “I couldn’t find out how much and what kind of jewelry it was.”

The claim was met with much skepticism. “The Fence editor is on speaking terms with Mrs. Robey,” Dr. B. U. L. Conner wrote, “and once when she won $2.30 at keno, she bought the Fence editor a nickel beer. This $100 to $200 a week stuff is pretty high for a lady of Mrs. Robey’s proclivities.”

For Vermillion, the crusade against gambling was personal. Vermillion told the court that his own son had been involved in gambling and had lost his job at a bank as a result. Another bank employee, whose name the Reverend couldn’t recall, had lost it all at the tables and took his own life. These were just some of the daily tragedies unfolding in the wake of open gambling.

Determined to put an end to it once and for all, the intrepid Reverend enlisted the help of Sam Wilt, a barber who dabbled in detective work. “I thought he would know about gambling,” Vermillion testified. “He’s been in the detective business.”

The Reverend, the barber, and a motley crew of concerned citizens visited the clubs themselves to prove there was gambling going on. Vermillion collected their affidavits and took them to the District Attorney, but the DA wasn’t having it, so he took them to the mayor, who referred him to the police chief. But Vermillion believed the chief to be compromised.

“I was standing on a downtown street,” Vermillion said, “talking with D. R. Miller, when a man whom neither of us knew approached us and told us that [Dave Lawson’s attorney] Mr. Fryer had said that the Police Chief was getting $750 a month payoff from the Knickerbocker Club.”

Justice Goggin was incredulous. “Do you mean a perfect stranger approached you men and volunteered that information?”

“Yes, we had never seen him before,” Vermillion replied.

Justice Goggin moved on, pressing Vermillion on his knowledge of pay-offs, but the Reverend could provide no direct evidence, only rumors and common gossip. The Justice scrutinized Vermillion’s assertion that grand juries had been packed, insisting to find out which lawyers had made such claims.

“The lawyer that first told me that is dead,” Vermillion said. “I was told that in picking grand juries, four men always were selected whose stand on certain issues was known, and they were chosen so that no indictments would be returned.”

Justice Goggin demanded names and details, but the Reverend buckled under the intense questioning. He was suddenly “too tired in mind and body” to answer anymore questions, saying he had been ill for two weeks. “Your Honor, you’ll have to give me time to rest and think before I can answer.”

It only got worse for Vermillion when he returned to the stand that afternoon. His relationship with barber/detective Sam Wilt was questioned. The county attorney revealed Wilt had a prior conviction on barratry and had been caught operating a gambling and shake-down operation of his own.

“Well, Reverend Vermillion, would you consider Mr. Wilt’s advice credible?”

“No, I wouldn’t,” Vermillion conceded.

Justice Goggin saved his sharpest criticism for Vermillion’s exit from the stand, condemning his open letter that kicked off the inquiry.

“I’d say, Reverend Vermillion,” the Justice said, “that anyone writing such a letter on the evidence you have testified to here should be censured. Our laws recognize that fact and have provided a fine and imprisonment. In my opinion, you are guilty of criminal libel against the men named in your letter. You have no right to debase their character. It is up to them whether they file a complaint against you.”

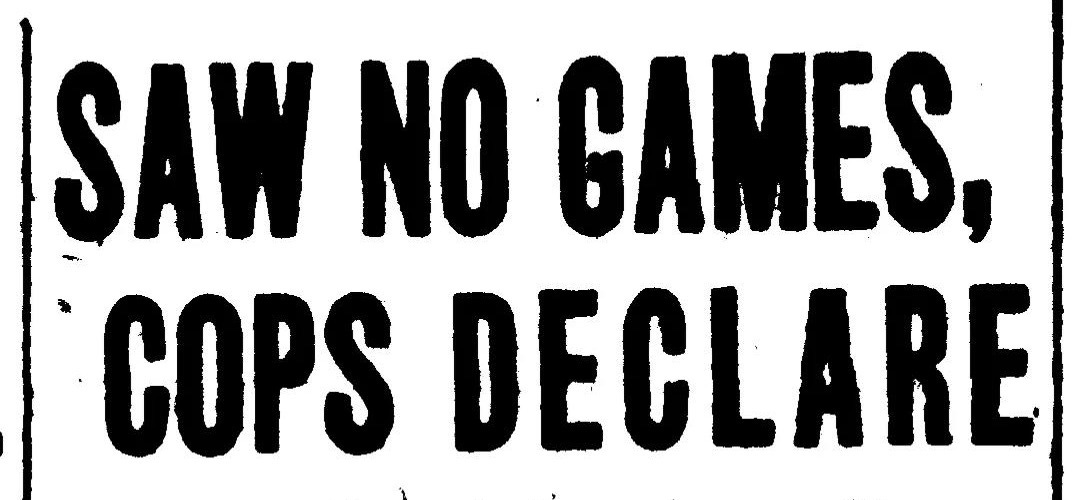

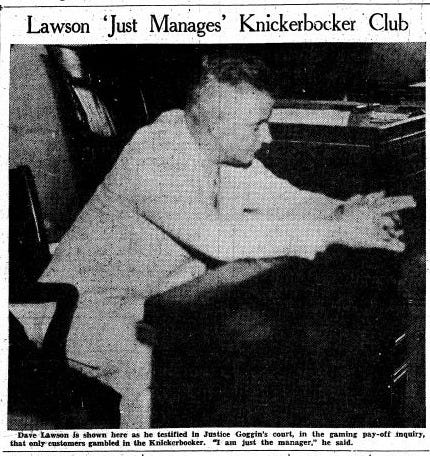

The fireworks continued to fizzle when Dave Lawson and the other gamblers took the stand. Despite their immunity deal, there were no major revelations. “I am just the manager,” Lawson said of the Knickerbocker. “The customers just go back and start shooting dice. We lend them the equipment some times.”

Justice Goggin threatened Lawson with perjury if he didn’t come clean. But Lawson insisted he knew nothing of a pay-off. The court of inquiry was shaping up to be a flop.

“Nobody knows nothing except what somebody said,” wrote Dr. B. U. L. Conner. “The Court of Iniquity so far has demonstrated nothing except that such a court is a good way to make idle gossip privileged matter. Why not turn every bridge club in town into the same thing?”

Who is Detective Jeffrey?

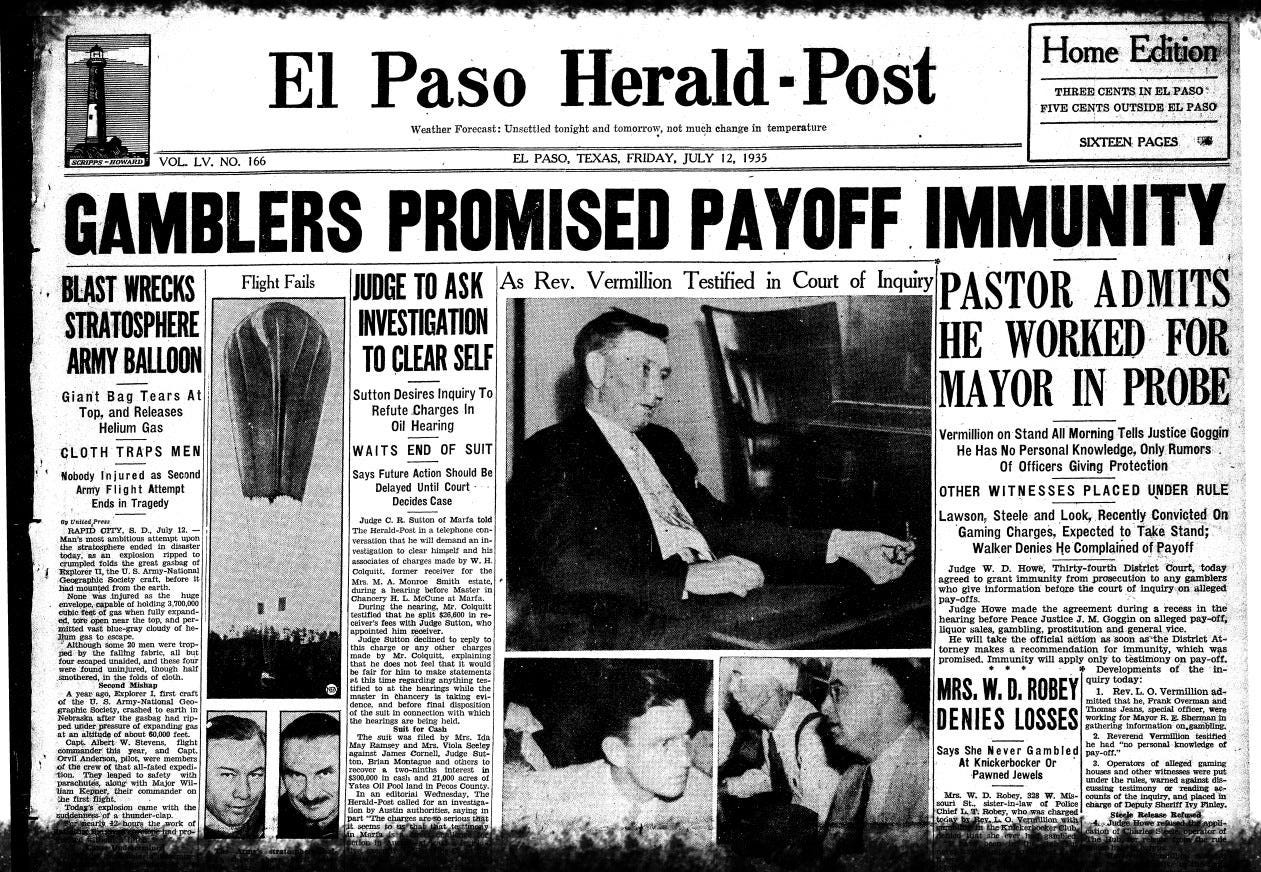

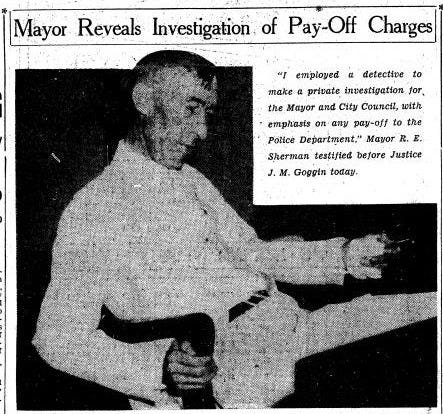

The drama picked up with Mayor Sherman’s much anticipated testimony. Justice Goggin began by grilling the Mayor on his vice policies, ranging from liquor to gambling to prostitution. The mayor shrugged off concerns over liquor sales, Repeal had passed after all. And he supported the long-held city practice of keeping prostitution “under control and medical supervision” in a red-light district. But when it came to gambling, it was well known he had authorized raids for years.

Justice Goggin hammered the mayor on why he hadn’t worked harder to shut down gambling at the Knickerbocker. “Why didn’t you put a man at the club?” he asked.

“It would have been too expensive,” Mayor Sherman replied.

“Why didn’t you order daily inspections of the club?”

“That could have been done - the idea never occurred to me.”

A nervous hush fell on the courtroom when Justice Goggin put the million dollar question direct to Mayor Sherman: “Have you ever been approached with any bribe in regards to gambling?”

Mayor Sherman hesitated, looking up at the ceiling before responding. “I have never been approached directly,” he finally said with a smile, “but I believe I know when I am being felt out.”

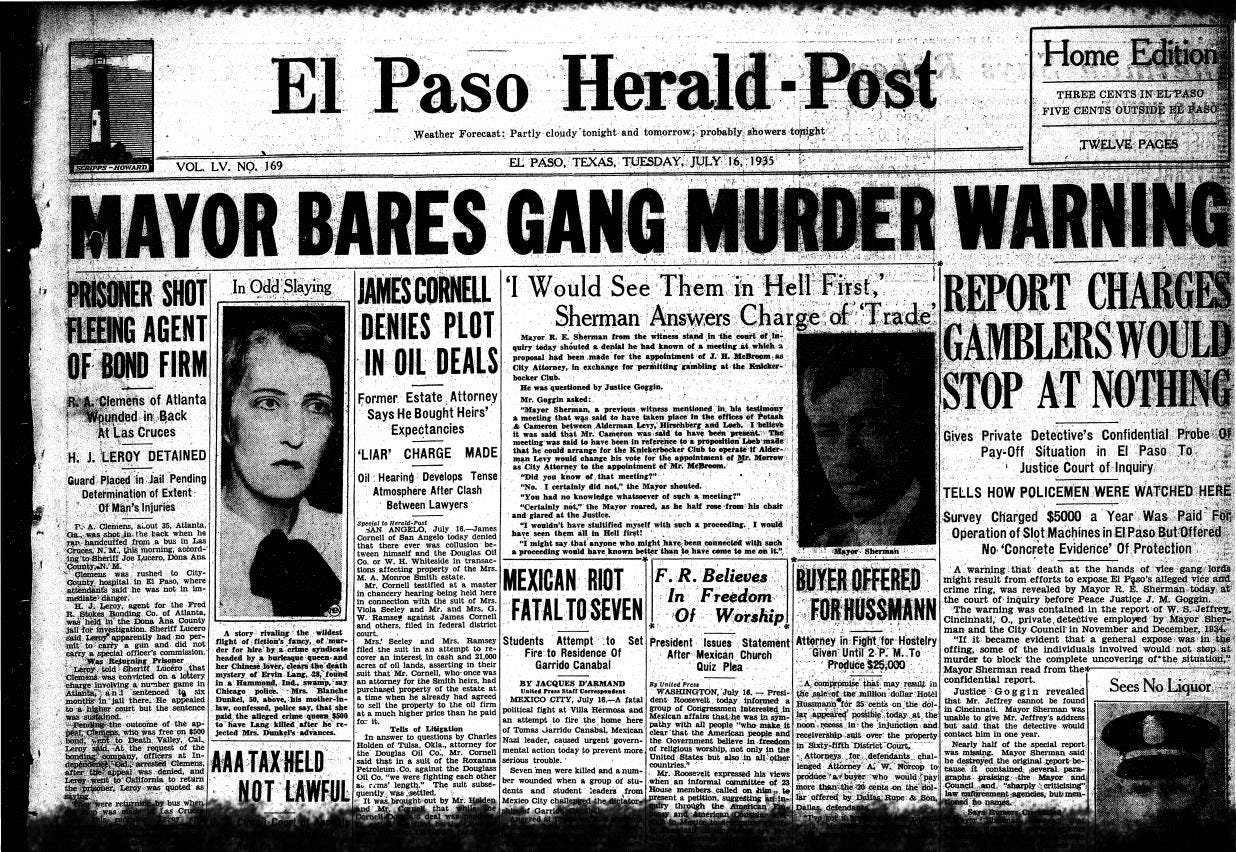

Then, on Mayor Sherman’s second day of testimony, he dropped a bombshell: attempts to expose El Paso’s vice rings could result in death at the hands of vice gang lords. “If it became evident that a general expose was in the offing, some of the individuals involved would not stop at murder to block the complete uncovering of the situation,” Sherman read from a prepared statement.

“The knights of the green cloth have been in the saddle for 25 years,” he continued to read. “El Paso is wide open with gambling, bunco, and narcotic rings extending their unlawful activities even into the private and business life of the city.” The gambling epidemic was “beyond the possibility of the police to cope with the situation.”

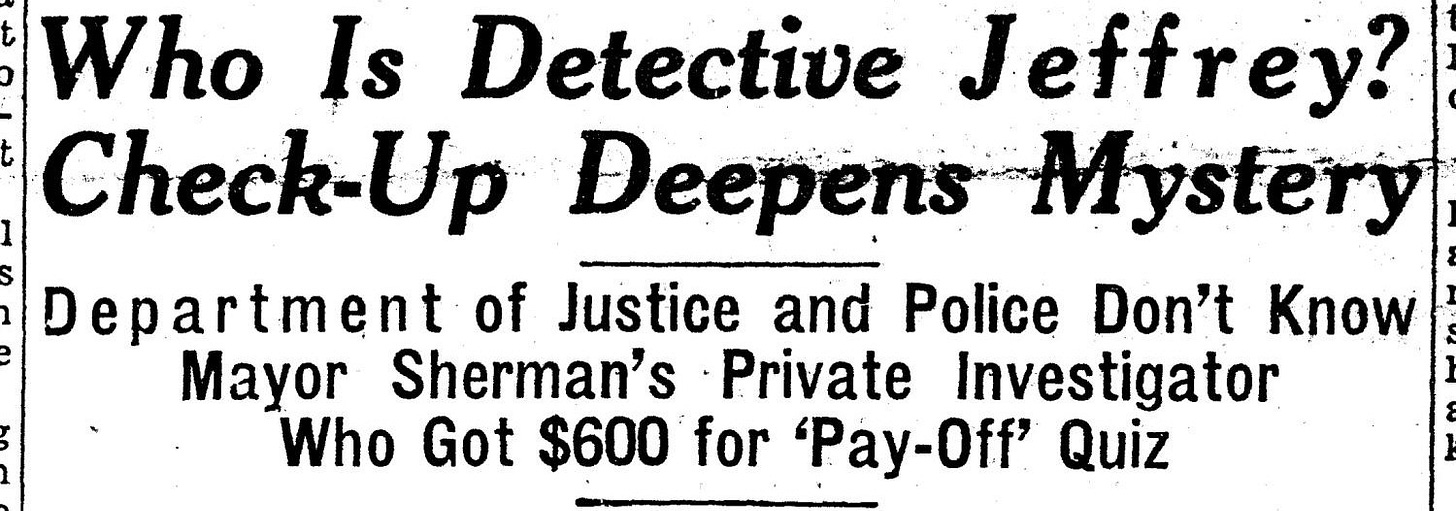

These were the findings of W. S. Jeffrey, a private detective brought in from Cincinnati by the mayor to investigate alleged pay-offs to the police department. The mayor and city council hired Mr. Jefferey of the “American Detective Agency” to conduct a twelve-day investigation and issue a report for a fee of $600, or $120 per page for the five page report (in 1933 dollars). And while no concrete evidence of pay-offs was uncovered, the report found “indications” of such.

There was only one problem with the report, detective W. S. Jeffrey of Cincinnati, Ohio wasn’t real. Justice Goggin revealed that the court could not locate Mr. Jeffrey. No one in Cincinnati or at the Department of Justice had ever heard of him. Mayor Sherman said he had a letter of recommendation from Houston where Jeffrey claimed to have done some work but Houston officials and private detective agencies there never heard of the man. The detective did not provide an address to the mayor but told him he would contact him in one year.

Dr. B. U. L. Conner had a solution. He offered dinner and drinks to anyone who could produce information leading to the detective’s location. “It is simply a case of dinner for two if Mister Jeffrey can be brought out of his skidoo.” The mystery went unresolved.

Sundays with Loeb

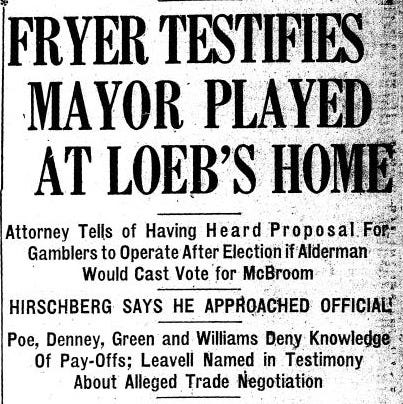

W. H. Fryer, attorney to Dave Lawson and the other gamblers, flipped the narrative on Mayor Sherman with his testimony. Fryer alleged that slot machine operator Isidore Hirschberg met with City Alderman Ben Levy to discuss a proposition wherein gambling would be allowed to run if Alderman Levy switched his vote to the gamblers’ preferred candidate for city attorney. Testimony from Hirschberg implicated boss fixer Leo Loeb in the deal, although it was unclear to all involved just how the deal would work.

Regardless of the deal’s efficacy, Mayor Sherman would have been well aware of it, according to Fryer. “Leo Loeb was the Mayor’s companion,” Fryer said, “and Mayor Sherman played poker at Loeb’s home every Sunday.” The two were old friends and Sherman’s firm had even sold Loeb his property in town, Fryer claimed.

Mayor Sherman returned to the stand to respond to Fryer’s allegations, denying playing poker at Loeb’s house. “I have not seen or spoken to Mr. Loeb for six or seven years and never have played poker since I have been in El Paso - 24 years,” he said. The mayor declined to comment on whether his firm had sold Loeb property.

Alderman Levy, near shouting, denied the whole thing, testifying that he was never approached about the trade. “No sir - never! I wish to state that the name of Loeb was never mentioned,” Levy said. “I wouldn’t know him if I saw him come through that door - I want that distinctly understood.”

Leo Loeb was out of town and could not be reached.

Justice Goggin had heard enough hearsay and ended testimony. He kept the gamblers on notice by recessing the court instead of adjourning, threatening to re-open the court when Loeb returned to El Paso. The Justice instructed the district attorney and county attorney to study the record with an eye toward perjury charges. Despite the stern warnings, the case appeared closed.

“Thus the El Paso gambling fraternity is fully vindicated,” wrote Dr. B. U. L. Conner. The end result after hours of testimony boiled down to “nobody knows nothing about no payoff.”

Nevertheless, Mayor Sherman claimed victory. He said he believed the sentiment of El Pasoans toward gambling had gradually changed as a result of his campaign. The critics and the naysayers, in his view, had come around.

“I have had numerous expressions from business men and others who admitted that I was right,” the mayor proclaimed.

Maybe the mayor had a point. During the inquiry, the Herald-Post reported gambling was experiencing the worst slump since 1931. Bar operators told the paper the scare created by the inquiry had reduced their business more than half.

“It’s the worst Saturday night the place had seen in two years,” Dave Lawson told the paper.

In his year-end statement, Mayor Sherman issued a warning to the gamblers for 1936, promising them the same treatment they got in 1935. Gaming would not be permitted in the new year. Better times were ahead.

“But times will be no better for the gamblers,” the mayor said. “I expect to see an increase in all types of business, save gambling.”

Next time on Borderland Vice: it’s business as usual for the gamblers of El Paso; Dave Lawson comes up with a new scheme; and a new player in town seeks to smash the Knickerbocker’s monopoly. Come back for Part 2 when we meet Frank Ardovino and slip into New Mexico.

![Or Give Me Death Industries [substack edition]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!rF5C!,w_80,h_80,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep,g_auto/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F6790ca65-d171-497c-85d0-70c43dab81be_736x736.png)

![Or Give Me Death Industries [substack edition]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!C8FR!,e_trim:10:white/e_trim:10:transparent/h_72,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F918e6633-25ca-4b95-b28f-d4d1bfeccce8_1344x256.png)