Part 3 in a three-part series on the last gasp of open gambling in the Borderland. This one gets a little dark. [Read Part 1 & Part 2 here]

Gutters and Strikes

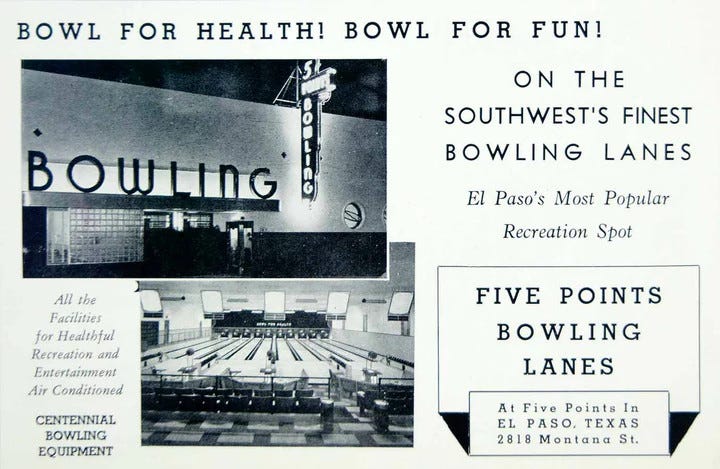

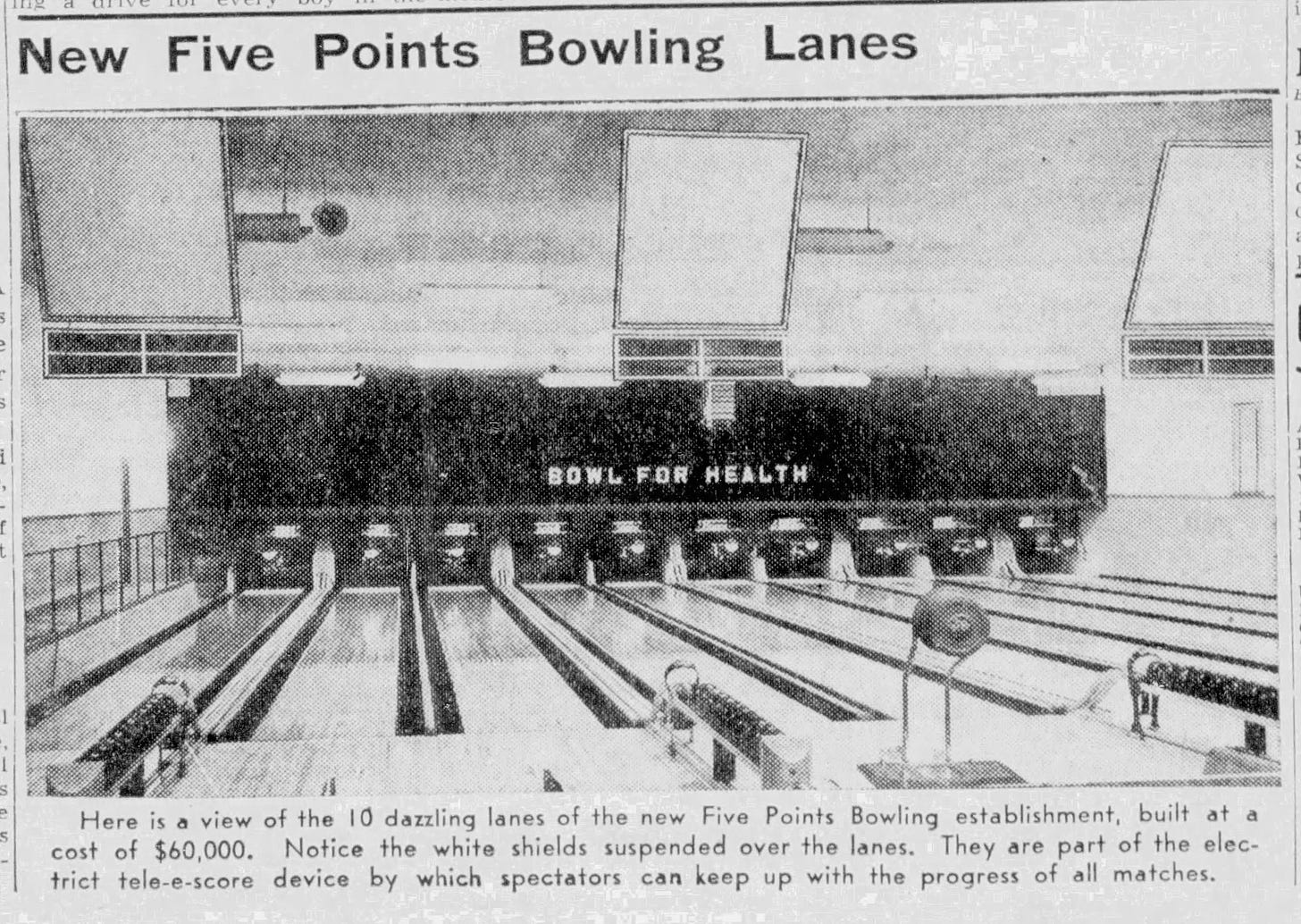

The Five Points Bowling Lanes opened to great fanfare on a cool October morning in 1940. All of El Paso was invited to attend the gala opening of the Southwest’s finest bowling alleys. Much had been made of the $60,000 price tag for the 10 dazzling lanes The alley was fully loaded with “the finest equipment money can buy,” such as the Electric Tel-E-Score that allowed spectators to follow the score, and the state-of-the-art Tel-E-Foul, an electric “eye” that detected fouls using an electrical beam. Dave Lawson had done it; he had built his shrine to bowling and delivered the great game to the masses.

Praise poured in for Five Points Bowling Lanes. The El Paso Herald-Post sports page called it the most modern plant in the Southwest. There may have been bigger lanes in the country, but none nicer. The Five Points club would be the answer to the American Bowling Congress’ long standing criticism that El Paso bowling alleys were merely fronts for illicit activity. The new lanes would improve bowling’s image and boost league play in El Paso.

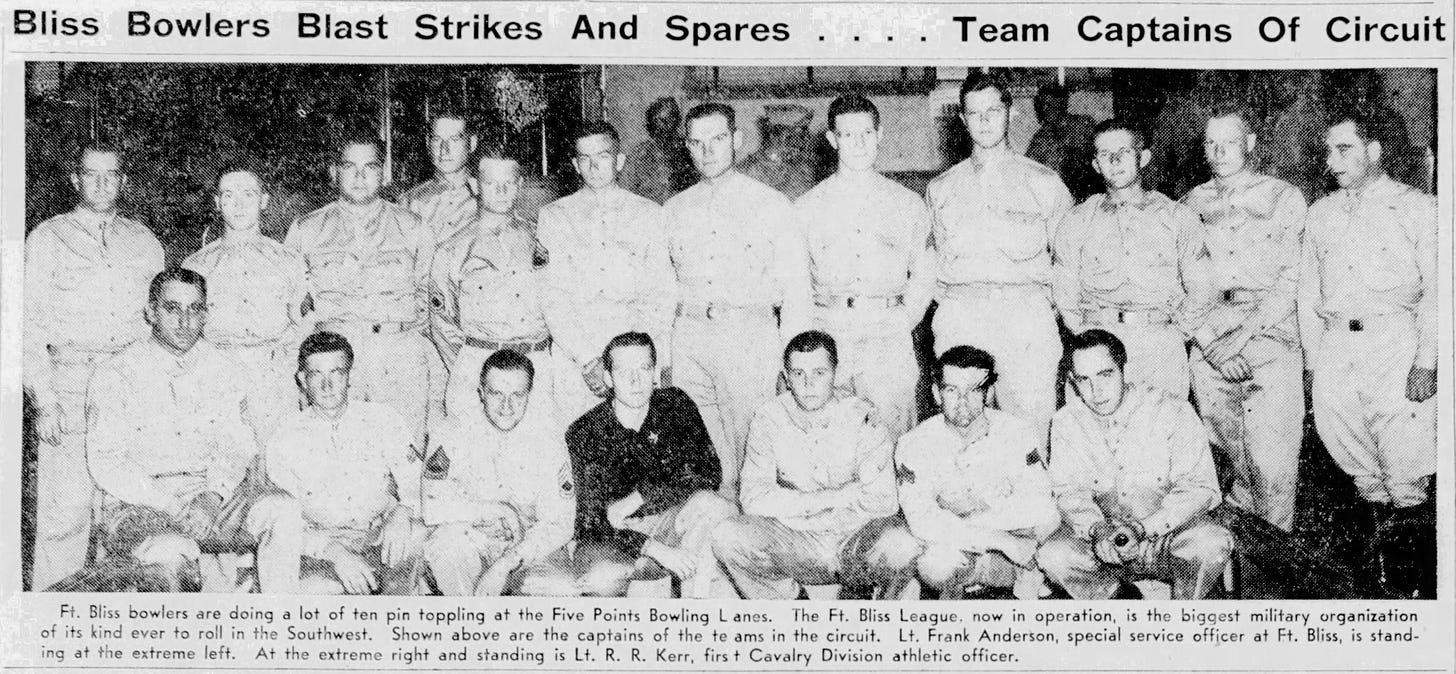

The lanes proved wildly popular for both players and spectators; so popular that six additional lanes were added within less than a year. League play exploded, as predicted, capturing the attention of the El Paso sports pages. City tournaments, charity tournaments, and a league for the soldiers at Ft. Bliss all found a home at Five Points. The lanes were a draw for tourists and even visitors from outer space. In 1947, patrons claimed to have witnessed a flying disc hovering over the area.

With the success of Five Points Bowling Lanes and the legitimization of bowling in El Paso, one might think Dave Lawson had gone straight, maybe even turned a corner. But one might also wonder what kind of a man names his dog Bookie.

Five Points Bowling Lanes built a reputation as a healthy, family outing, and yet, gambling paraphernalia managed to find its way inside. Slot machines and punch boards, a lottery-type game involving a board with circles covered in paper hiding a numbered ticket, were seized at the bowling alley. And Dave Lawson was still running the Knickerbocker Club, where business went on as usual. As always, modest fines were paid and the games rolled on.

The Charmed Life of the Valley Country Club

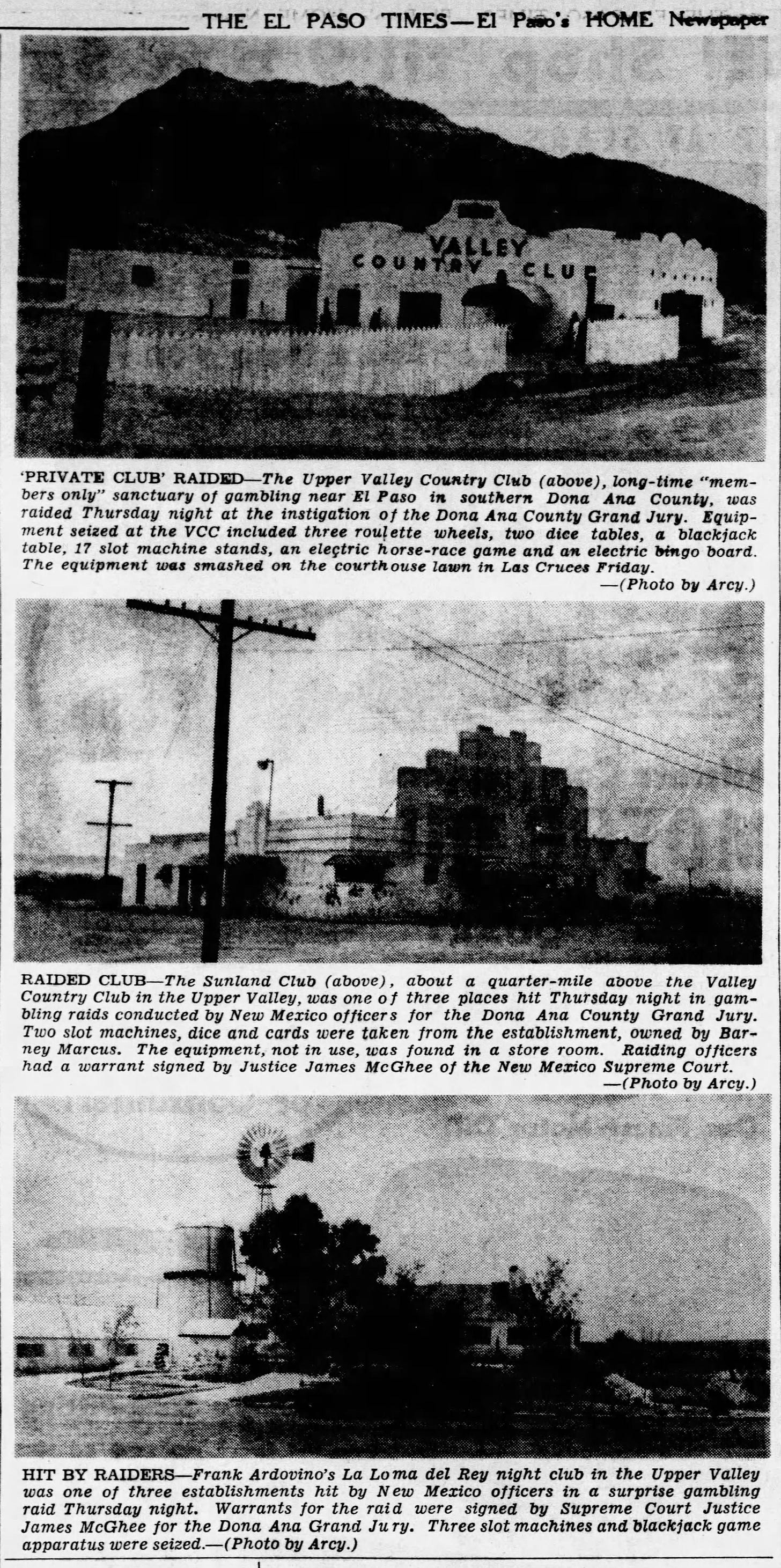

Across the state line, business was going well for Frank Ardovino. No longer feuding with Dave Lawson, and now enjoying support from officials, Ardovino was free to expand. By 1948, he had a stake in three different clubs: the Upper Valley Country Club, the Mecca Club, and his personal night club, La Loma del Rey, which doubled as his residence. Due to some past indiscretions, Ardovino was technically prohibited from operating a club in New Mexico. As such, he only owned the building where the Mecca club operated, he didn’t run it. Or, in the case of the Valley Country Club, he merely worked in the kitchen.

Authorities seemed disinterested in Ardovino’s day-to-day activities at the clubs but they appreciated his company. Prominent local politicians and state officials from Santa Fe frequented the clubs and held memberships. Ardovino had come a long way since his war with Dave Lawson a decade prior.

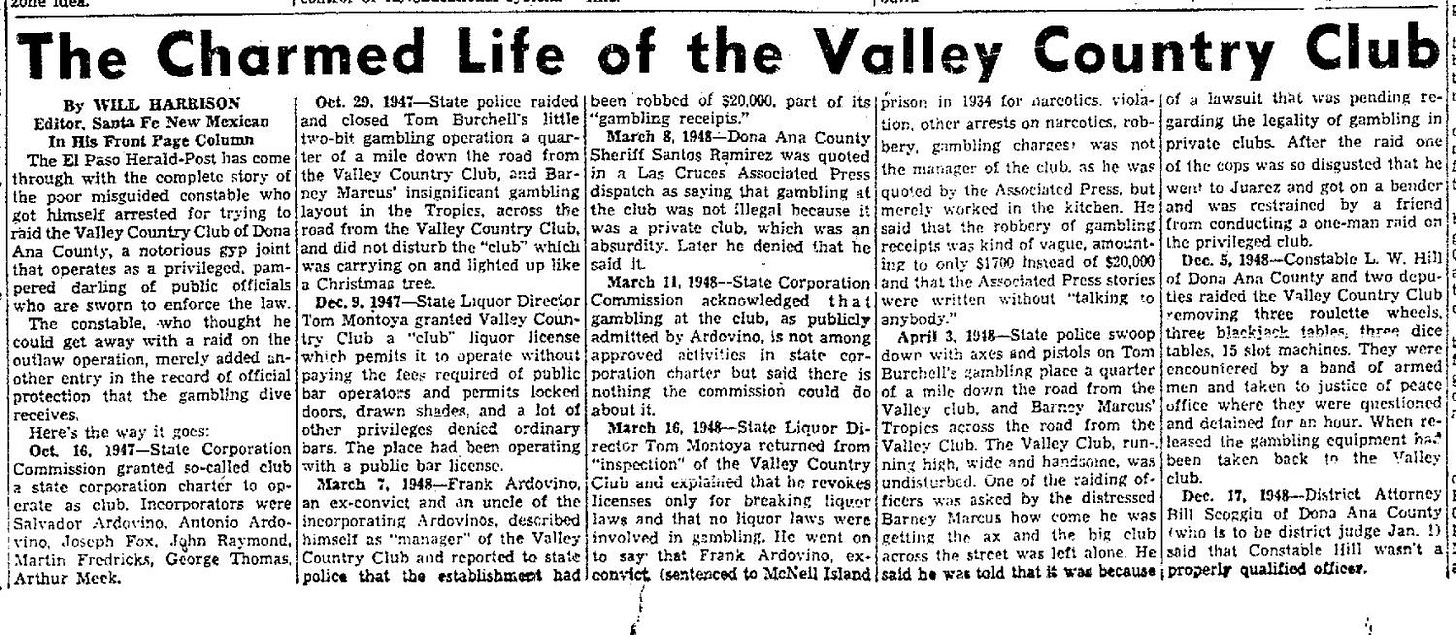

The protective halo surrounding Ardovino and his establishments shone brightly. But the Valley Country Club’s perceived immunity as a private club was put to the test in the spring of 1948. New Mexico authorities shut down two small-time gambling operations while the Valley Country Club carried on, “lighted up like a Christmas tree.” The double standard was so conspicuous it drew front page condemnation by the editor of the Santa Fe New Mexican. New Mexico Governor Thomas J. Mabry weighed in, pressuring Doña Ana County officials to act.

The county claimed their hands were tied due to a pending lawsuit on the legality of gambling in private clubs. Doña Ana County Sheriff Santos Ramirez was quoted as saying gambling at the club was not illegal because it was a private club then later denied making the statement. New Mexico’s Corporation Commission declined to act, saying they had no authority to revoke the club’s charter since their paperwork was in order. The State Liquor Director said he could do nothing since no liquor laws covered gambling.

Under immense pressure, the county caved and raided the Valley Country Club. But the club was ready for them. The raiding party was greeted by a well-groomed, courteous hostess who showed them around. Sheriff Ramirez found no evidence of gambling.

“We saw some bingo cards but nobody was playing,” Sheriff Ramirez said. “I don’t know whether bingo is gambling or not.”

After about 45 minutes of hanging around, talking to patrons, and checking membership cards, he left.

“I guess our raid Saturday night caused them to move out their equipment,” he said, referring to a raid on a nearby club.

The law wasn’t Ardovino’s only concern. That same spring, armed men entered the club using member keys. The bandits tied up the staff and broke open two safes, stealing $20,000 in gambling receipts. The men got away, speeding off in a mud-splattered Chevrolet.

Despite these setbacks, gambling looked to be flourishing in the New Mexican desert. Not only were the most powerful men in Santa Fe routinely making the four-hour drive down to Las Cruces to gamble, but deep pocketed, well connected investors from out of state were moving in.

In the late 1940s, Las Vegas becoming the preeminent gambling destination in the country was not a foregone conclusion. Frustrated with the pace of progress in Nevada, some of the bosses from the syndicates back east started looking at New Mexico as a friendlier alternative. Notorious mobsters like Benjamin “Bugsy” Siegel and Meyer Lansky were buying up real estate for casino sites in Santa Fe. FBI files released decades later revealed the Cleveland Mob had stakes in several New Mexico gambling operations, including the Valley Country Club and La Loma Del Rey.

With complicit elected officials and a syndicate bankroll, the sky looked to be the limit for gambling in New Mexico. Las Cruces was set to become the Reno to Santa Fe’s Las Vegas, were it not for a grizzly discovery in the desert.

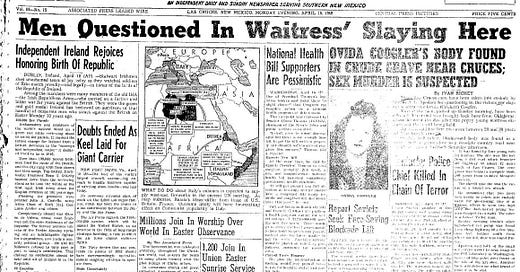

Who Killed Cricket Coogler?

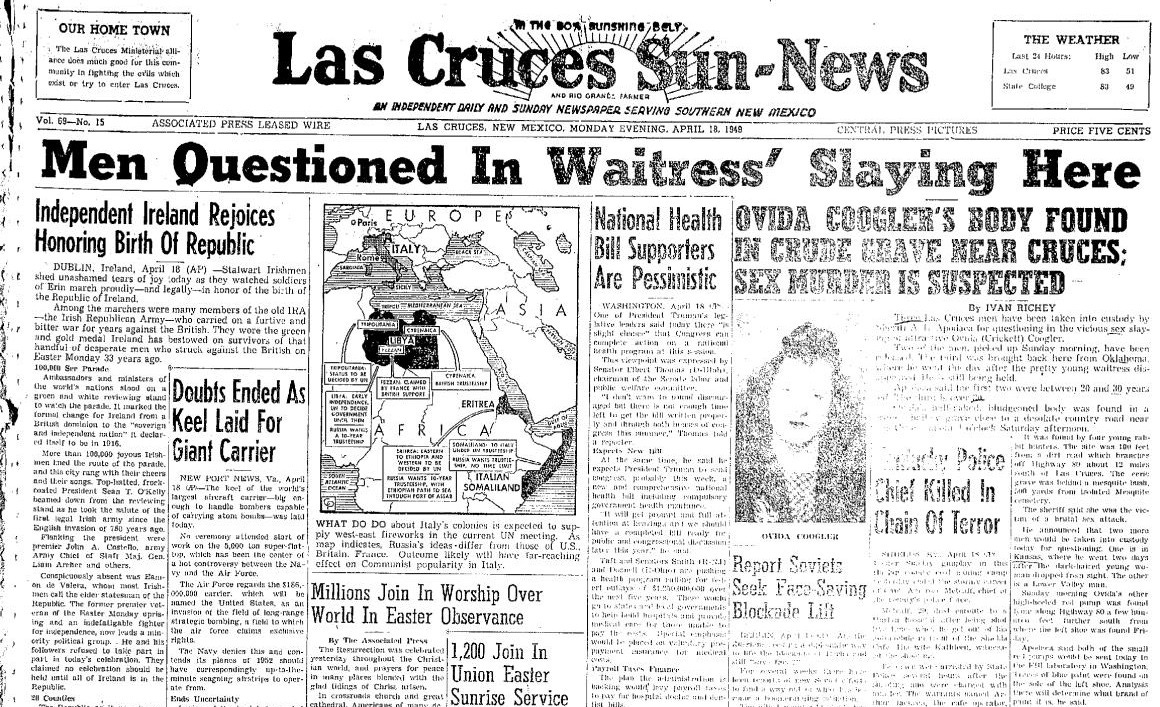

On April 16, 1949, four young rabbit hunters stumbled upon the half-naked, bludgeoned body of a young woman. She had been partially buried in a shallow grave in the desert south of Las Cruces. Her name was Ovida “Cricket” Coogler, so nicknamed for the clicking sound her red pumps were said to make on the sidewalk. Cricket was only 18 years old and had been missing for over two weeks. She was last seen in Las Cruces, getting into an unidentified car outside the DeLuxe Cafe at 3 a.m.

Cricket lived what was, in the parlance of the time, known as “high-risk lifestyle.” A high school dropout, she worked as a waitress and possibly an escort. She gained a reputation as a thrill seeker who liked to have a drink and a good time, anything to escape her family’s crushing poverty. The doomed party girl was often seen in the company of older men, including politicians, eager to supply the drinks.

On the night of her disappearance, Cricket frequented several clubs in the Las Cruces area and had been seen with multiple men, each now a suspect. Speculation swirled around the politicos. Some believed recently elected Sheriff A.L. “Happy” Apodaca, a former prizefighter, had the murder covered up or even did it himself. When the body was discovered, Apodaca was quick to declare she had been raped and murdered then had her buried without an autopsy.

The horrific crime and its poor handling shook the community and made national headlines. Needing to act, Sheriff Apodaca secretly jailed a suspect who had been spotted drinking with Cricket on her last night. The suspect was Jerry Nuzum, a former star halfback at New Mexico A&M drafted by the Pittsburgh Steelers.

Nuzum was held on what Apodaca called “voluntary arrest” for three days. Nuzum had “volunteered” to be held after being told he would be charged with murder if he objected or tried to hire a lawyer. It was not until El Paso reporter Walt Finley decided on a whim to investigate the case that the arrest was discovered and made public. Apodaca initially placed Nuzum in solitary but then decided to clear him of all charges and set him free.

Unfortunately for Nuzum, the case didn’t end there. Edwin L. Mechem, a candidate for governor of New Mexico in 1950, had solving Coogler's murder at the top of his platform. To Mecham, it was "the Nuzum case." Mechem became governor and Nuzum once again became a suspect.

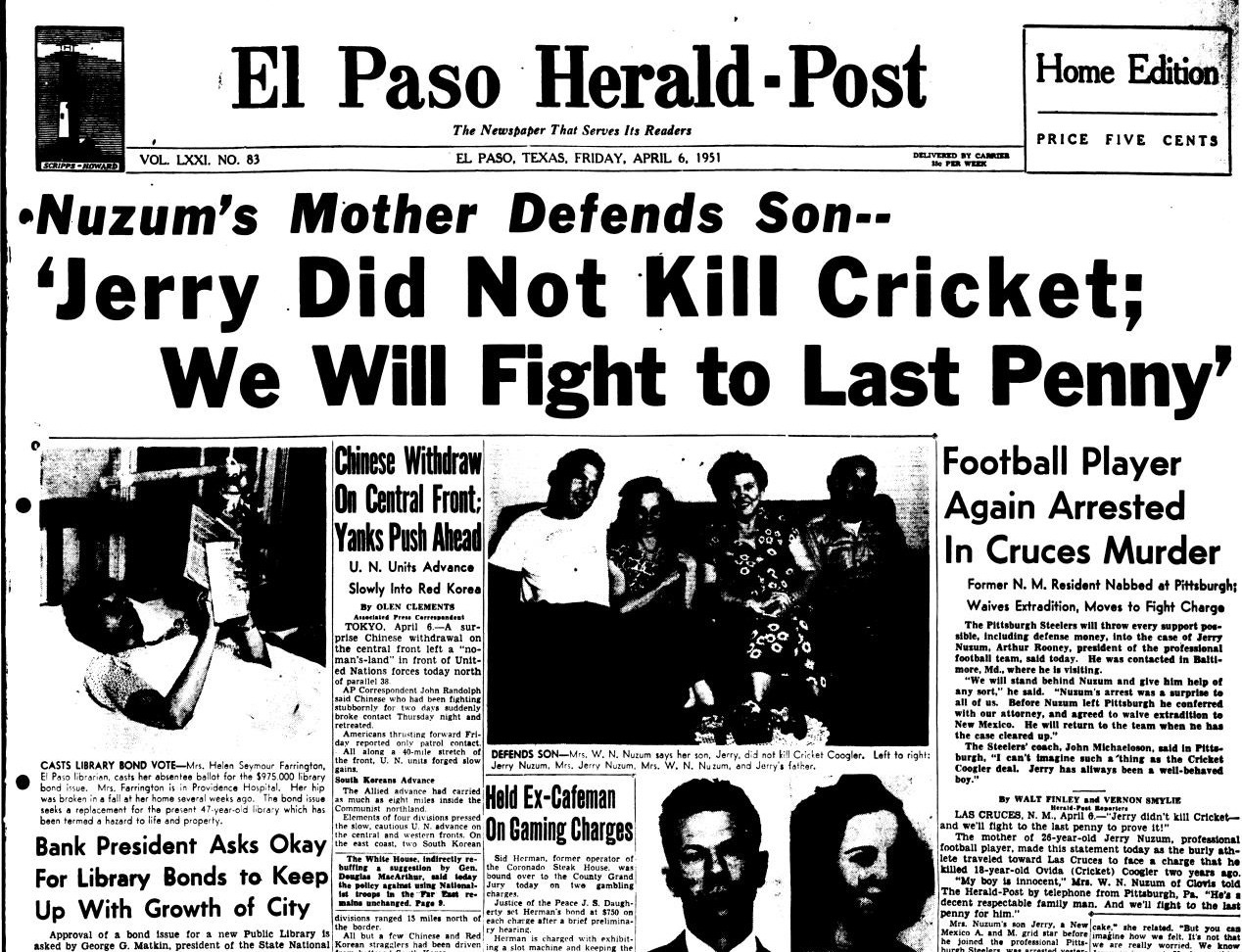

In 1951, Nuzum was arrested and charged with Cricket’s murder. It was the first high-profile murder trial involving an NFL player. Steelers owner Art Rooney and head coach John Michelosen backed Nuzum.

"I can't imagine such a thing as the Cricket Coogler deal. Jerry has always been a well-behaved boy," Michelosen said.

After a costly trial, Nuzum was acquitted based on a lack of physical or concrete evidence connecting him to the murder. Nuzum had a decent alibi, attested to by his wife and landlady. And while witnesses did report Nuzum had tried to force Cricket into his car; another witness testified that he had intervened, stopping Nuzum. Helping Nuzum’s case was a report from a Las Cruces policeman who spotted Cricket later in the night getting into a different car than Nuzum’s. Yet another witness claimed to have seen state police chase and beat Cricket before putting her into a police car.

With conflicting stories and flimsy evidence, the case fell apart and Nuzum was set free. But the trial would haunt him for years. It would take 20 years to pay off his legal fees and the stigma of being a murder suspect cut his NFL career short. He did not play pro-football again after the trial.

Nuzum was not the only innocent person to be railroaded by Happy Apodaca. Wesley Byrd, a Black man aged 27, experienced far more severe treatment. Byrd told reporter Walt Finley the sheriff kept him in jail for 10 days without allowing him to notify anybody. Much worse, Byrd said sheriff's deputies and the state police took him to the desert and tortured him for a confession, squeezing his testicles with a bicycle lock.

All of this was too much for the public to bear. A special grand jury was called and swiftly indicted Happy Apodaca on ten counts ranging from gambling, to failing to account for federal money, to the attempted rape of a 15 year old girl. A jury recommended his ouster. Happy bargained away his elected office to avoid criminal convictions.

Then, J. Edgar Hoover took an interest in the case and dispatched the FBI. The torture of Wesley Byrd resulted in the first federal convictions for police violations of a suspect’s civil rights. Apodaca, his deputy Roy Sandman, and former State Police Chief Hubert Beasley were all convicted and served time in La Tuna prison. Sandman later committed suicide. Apodaca and Beasley received pardons from President Harry Truman.

The grand jury investigated every bar Cricket was believed to have drank in the night she went missing, resulting in a slew of indictments on charges of gambling and selling liquor to minors. The investigation expanded, issuing more indictments, 58 by the time they were done.

Justice of the Peace T. V. Garcia was indicted on charges of embezzling state funds and for his role disrupting the attempted raid on the Valley Country Club the prior year. Other sensational indictments included the chairman of the Board of Doña Ana County Commissioners and the chairman of the New Mexico Corporation Commission. Time magazine remarked that the indictments “brought the cold sweat of apprehension springing to the brows of many a high-placed gambler and politico.”

Frank Ardovino was not immune to the new fervor for reform. His clubs faced raids, indictments, and ultimately pad locks to restrict gaming. The golden era of official sanction had come to a crashing halt.

The investigations made a lot of noise but never came close to solving the murder and bringing justice to Cricket Coogler. After 75 years, the case remains cold, likely rendered unsolvable by Sheriff Apodaca’s botched investigation. If a sliver of justice did emerge from the tragedy, it was the purging of the mob and at least some corruption from the New Mexico state government.

“The brute who buried Cricket Coogler in the desert also buried the ambitions of the racket,” wrote E. M. Pooley in an editorial for the Herald-Post. “And, should it become necessary, Cricket’s ghost will come back to haunt them.”

Lawson Auto Sales

While New Mexico was cleaning house, Dave Lawson was getting into a new line of work in El Paso. In March of 1951, a blurb in the paper announced Lawsons entry into the automobile business. Lawson Auto Sales was set to open on Montana street. Maybe the wave of reform reverberating throughout the region in the wake of Cricket’s murder had set Lawson on a new course. Now in his mid-fifties, maybe he was ready to settle down and take on less illicit business. Or maybe he just needed a new front.

Later that year, an injunction was sought against Lawson Auto Sales, accusing Lawson of running a bookie joint. The telephone lines were disconnected until Lawson agreed to the injunction and posted a $2000 bond. Lawson just couldn’t quit the game.

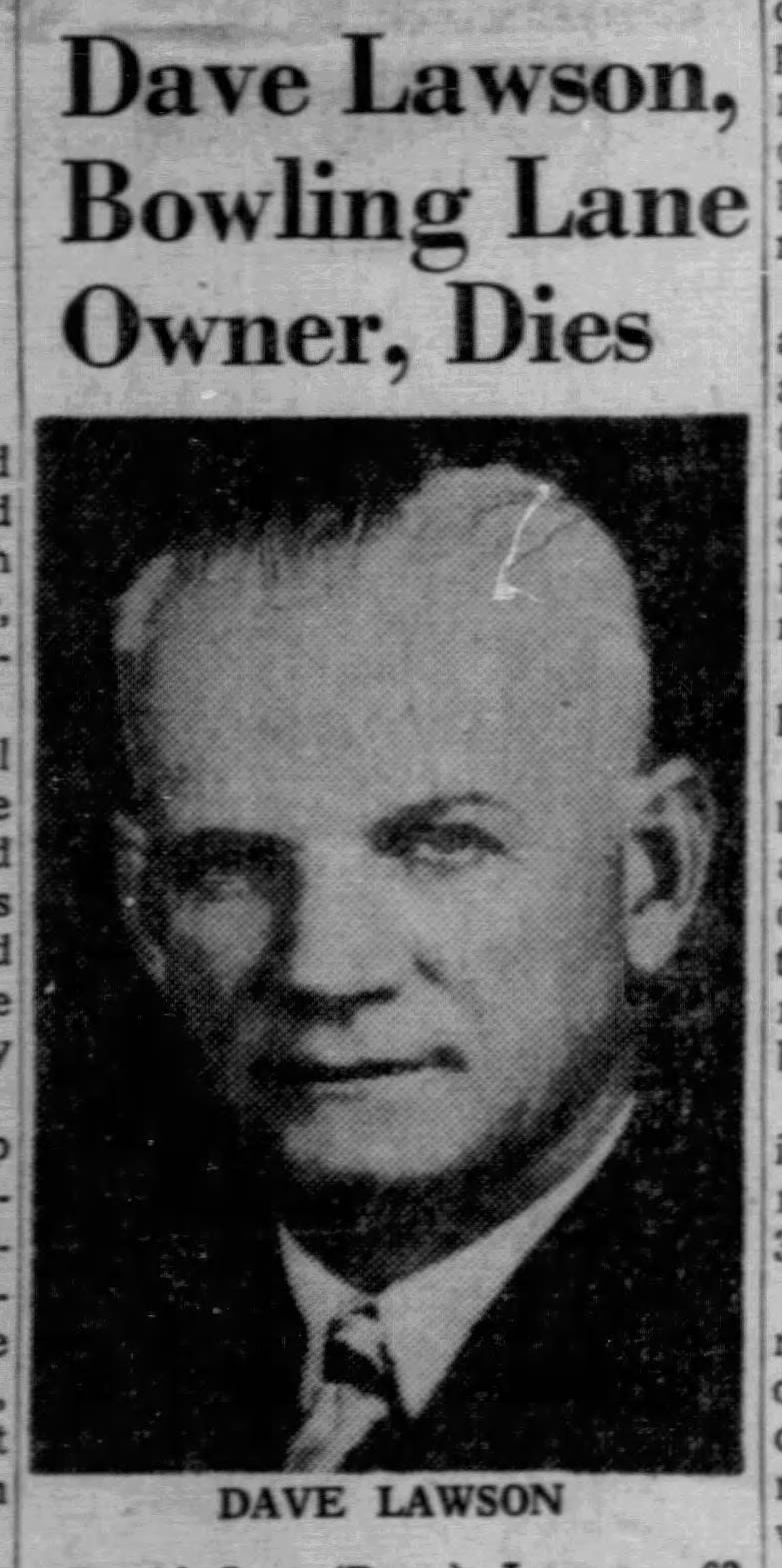

Dave Lawson’s luck ultimately ran out in March 1958. He died at age 63 following major surgery, leaving behind a widow and two daughters. He was remembered above all else as a bowler.

“It’s ironic that [Lawson] left us when bowling was at the peak of its success,” wrote Ray Sanchez for the Herald-Post in his remembrance. Lawson was one of the “finest and best-liked persons in the city.”

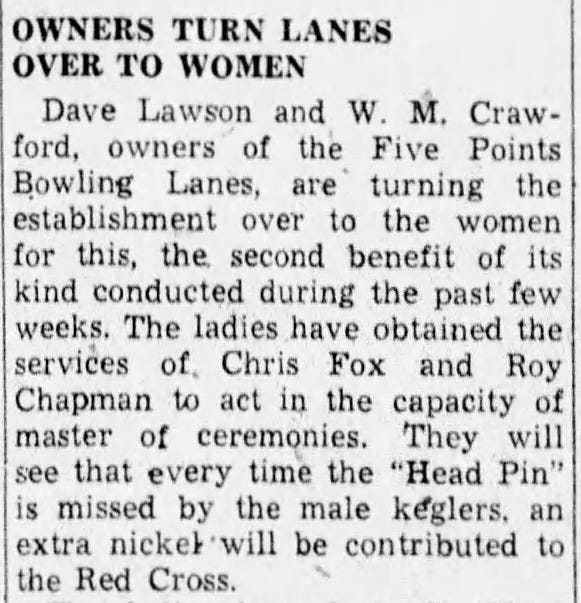

The Knickerbocker Club may have been El Paso’s most wicked gambling resort, but it was also a place where barriers were broken. Before 1935, bowling was largely cut off to women. Most men did not like playing with or against women. But Dave Lawson wouldn’t have it, he saw a future where all humans could enjoy the beautiful game.

Lawson started offering free bowling and lessons to women. Soon, women’s leagues sprang up at the Knickerbocker and Lawson himself organized the co-ed “Fair Sex” League. In 1936, the El Paso Women’s Bowling Association was founded and granted a charter from the Women's International Bowling Congress. El Paso’s women bowlers became active in the State Woman’s Bowling Association, bringing the state tournament to the Five Points Bowling Alley in 1948.

Sportsman, innovator, family man, scofflaw, philanthropist, and bowler - this was the legacy of Dave Lawson.

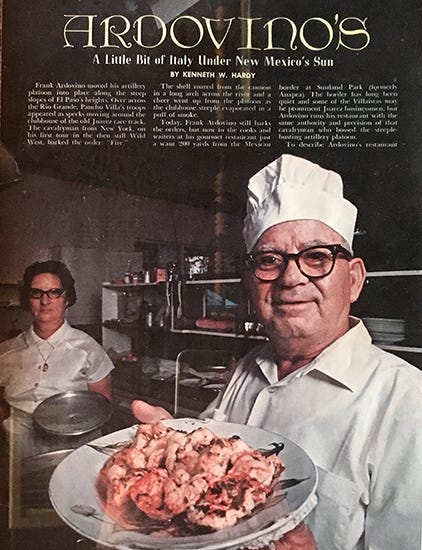

Italy Under New Mexico’s Sun

Frank Ardovino managed to shake off his legal troubles stemming from the raids. The New Mexico Supreme Court reversed a lower court judgement against Ardovino, finding the complaint to have been improperly drawn. But with the ongoing crusade against vice not slowing down, Ardovino decided to shift his focus.

The connective tissue between his many endeavors, from the Italian Village to the Mecca Club, was the food. In 1949, he added a kitchen to his La Loma Del Rey club and converted the residence into a dining room. Ardovino’s Roadside Inn, a fine dining establishment, was born.

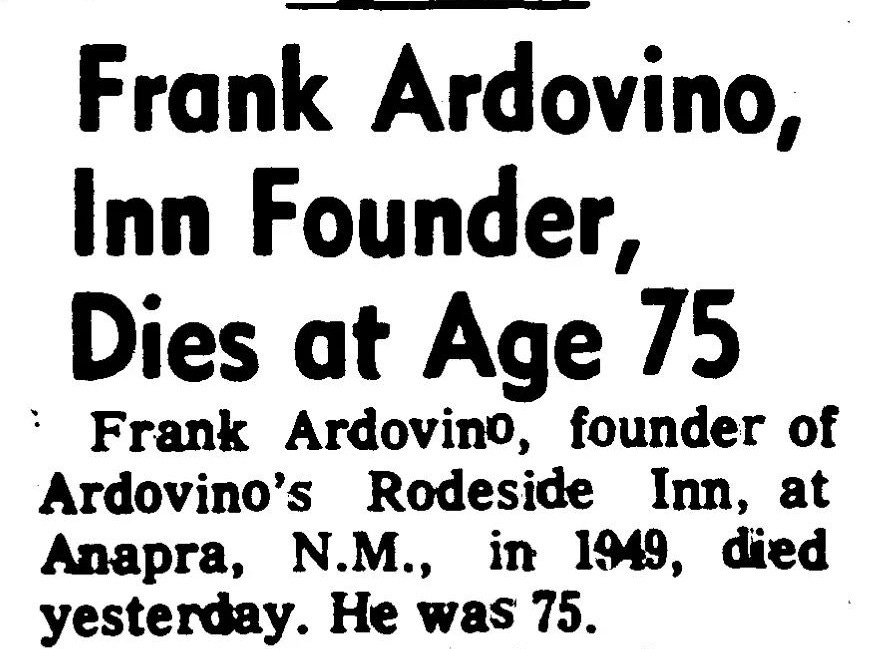

“I have to cook for these bums anyway, I might as well get paid for it,” Ardovino, or Uncle Frank, was heard to say. His restaurant stayed open until his passing at age 75 in 1972. The location reopened in 1997 by the current generation of Ardovinos as Ardovino’s Desert Crossing.

Frank Ardovino, a veteran of World War I, was buried in Ft. Bliss National Cemetery with military honors.

Sunset in the West

Ninety years since El Paso polite society began its final war on open gambling, wagering is more prevalent than ever. In 1959, less than a decade after New Mexico ran off the mob, a racetrack opened in Sunland Park, just miles away from where the Valley Country Club once operated.

Dave Lawson was once hauled before a judge for transmitting sports results out of a shack in New Mexico. Today, betting lines are delivered directly to one’s phone and wagers can be placed (in many jurisdictions) with the tap of screen. The major sports leagues receive millions of dollars in sponsorships from betting websites, traditionally known as bookies, and no one bats an eye. Even the family-friendly Disney corporation is running a book.

In the days before anyone with an internet connection (and possibly a VPN) could wager from home in their underwear, games of chance required taking a chance. They required putting on decent clothes, going out on the town, risking a raid, and living your life. The ease of technology has lead to an explosion of suckers and revived the old debates. No matter what shape gambling takes in the future, there will always be bookies, reverends, politicians, and suckers bouncing back and forth on the perpetually spinning roulette wheel of time.

![Or Give Me Death Industries [substack edition]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!rF5C!,w_80,h_80,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep,g_auto/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F6790ca65-d171-497c-85d0-70c43dab81be_736x736.png)

![Or Give Me Death Industries [substack edition]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!C8FR!,e_trim:10:white/e_trim:10:transparent/h_72,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F918e6633-25ca-4b95-b28f-d4d1bfeccce8_1344x256.png)

![Or Give Me Death Industries [substack edition]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!rF5C!,w_36,h_36,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep,g_auto/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F6790ca65-d171-497c-85d0-70c43dab81be_736x736.png)