Borderland Vice Pt. 2

Part 2: Casus Belli

Part 2 in a three-part series on the last gasp of open gambling in the Borderland. [Read Part 1 & Part 3]

Bank Night

Archie Dunn was down on his luck, the Depression had hit him hard. The father of seven was reduced to supporting his family on $21 a month in relief money. For three weeks he had gone without meals, all for a chance at a big break. Then, on a crisp November night in 1935, his prayers were answered. His name was called inside El Paso’s Wigwam Theater. It had finally happened. Archie Dunn had won Bank Night.

Mr. Dunn immediately bought popcorn and candy for his children, the first they had had in two years. He told the paper he would use the $450 in prize money to pay the notes on his home.

“I’m the happiest man in El Paso,” Dunn said.

A wave of prosperity had swept over El Paso in the form of Bank Night, a weekly contest operated by movie theaters across the country. The film industry and theater operators struggled with attendance during the Great Depression and saught creative means to bring back the crowds. Charles Yaeger, a former booking agent for 20th Century Fox, came up with a solution: throw in some light gambling and call it Bank Night.

The concept was simple. Anyone could enter their name in a registration book kept by the theater manager. Then, on Bank Night, a name would be drawn at random. The person called would have a set amount of time, just a few minutes, to appear in person on the theater stage to claim a cash prize. A ticket wasn’t needed to get in if called, allowing the theater to skirt lottery laws, but many bought tickets anyway to avoid having to wait in the lobby or outside.

Bank Night was a cultural phenomena, operating in 5,000 of the 15,000 theaters open in America in 1936. People packed movie houses for their chance at hundreds of dollars in prizes. If you were registered in the book, you could win any night. But there were drawbacks. For one, you had to be at the theater - or get there in a matter of minutes - to claim the prize. Going to Bank Night meant fighting the crowd and risking theft as robberies spiked around the drawings.

Cometh the hour; cometh the man. Dave Lawson, operator of the notorious Knickerbocker Club, stood outside the Plaza Theatre one drawing night, having a vision.

“I couldn’t have gone through that mob myself,” Lawson said.

Lawson had the solution. No longer would people have to suffer the aggravation of the crowd. Never again would a person find out the next day their name had been called while they were working the night shift. For just 10 cents on every $100 in prize money, Lawson would insure your prize up to $500.

“If a person holding one of my policies cannot reach the theater stage and is turned down by the operators, I will pay him the full amount of the purse if he presents his claim within 30 days,” Lawson said. “I don’t care whether the person whose name is called is in Hong Kong or Honolulu at the time of the drawing. Just so he makes his claim within 30 days, I’ll pay off.”

Lawson established the Winners Guarantee Company and sold policies at his club, drug stores, and coffee shops across El Paso. And the policies paid out, bringing relief to the masses.

“When my name was called I had a terrible sinking feeling,” said D. H. Graham, a farmer in the lower valley. “I had failed to get a guarantee.” But, thankfully, his wife had purchased a husband and wife policy, netting the couple $1000.

Competing insurance companies popped up, including the theater operators themselves. The secondary market surrounding Bank Night was so healthy it made more financial sense to stay home and cash in on multiple insurance policies than to go to the drawing.

Yet again, once Dave Lawson had a good thing going, The Man had to get in his business. State insurance regulators stepped in; it turned out selling insurance in Texas required a license. Lawson’s lawyer clarified that the “policies” were not technically an insurance product but rather guarantees, and thus not subject to the insurance department’s regulations.

Lawson went back and forth with the state but in the end it didn’t matter. In the summer of 1937, the State Court of Criminal Appeals determined Bank Night was an illegal lottery. Theater operators across Texas were threatened with fines if the drawings continued.

The Bank Night dream was over, and with it went the insurance side business. Lawson refunded his policy holders. In the roughly two years Bank Night operated in El Paso, theaters had given out $24,500 in prizes. It is unknown how much was paid out by insurance policies.

The Bank Night policy racket was just the type of clever scheme Lawson needed to stay a step ahead of the competition. His Knickerbocker Club had come to enjoy a near monopoly on El Paso’s gambling scene under the protection of boss fixer Leo Loeb, but the competition was getting restless.

Everything Under Personal Supervision of Frank Ardovina

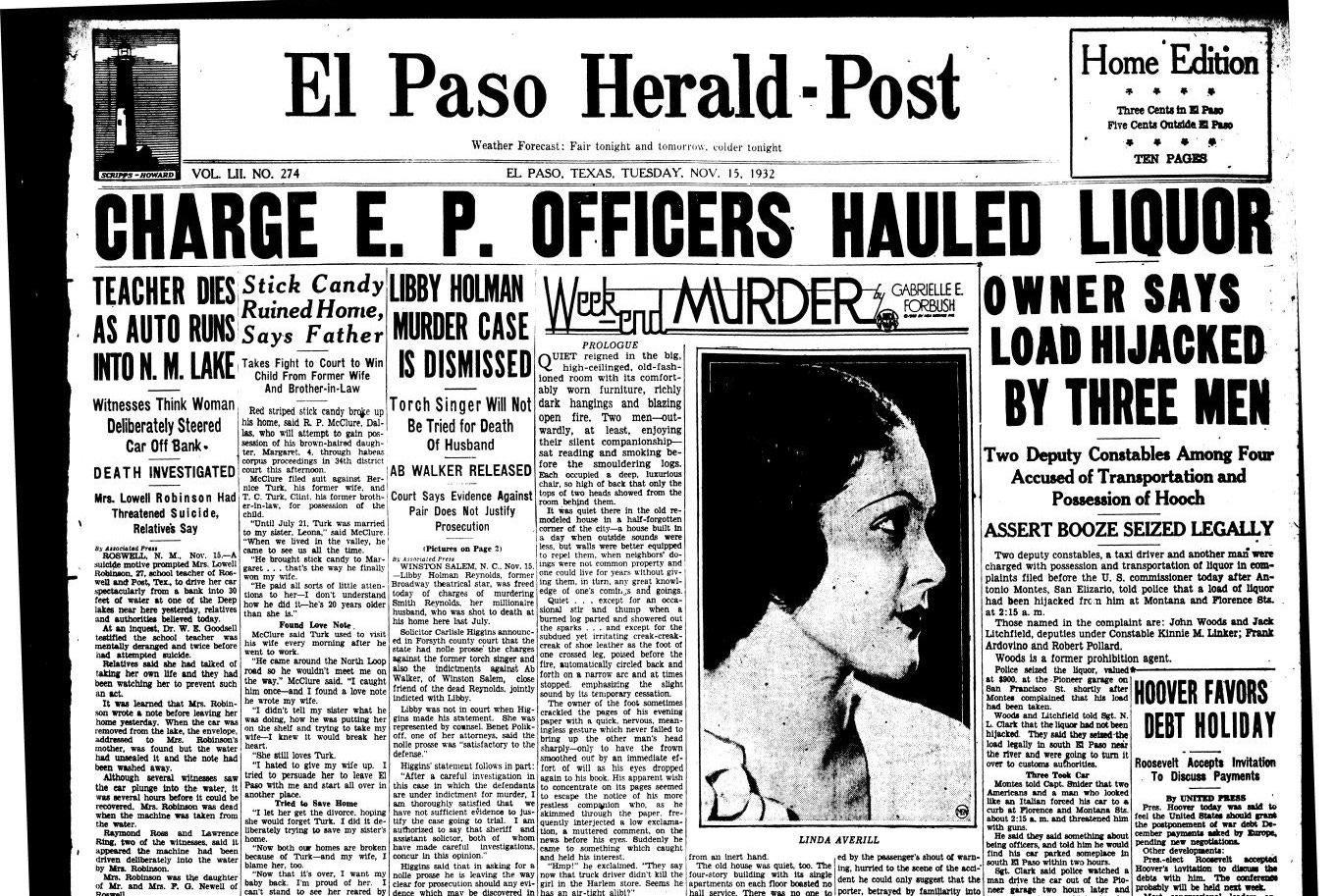

In the pre-dawn hours of November 14, 1932, Antonio Montes of San Elizario was driving a Buick loaded down with liquor along Montana Avenue when three men crowded around his car. One man blew a whistle. All three were armed with revolvers. They forced Montes’ vehicle to the curb and proceeded to search him at gunpoint. Naturally, they discovered the liquor, confiscated it, and loaded it into their own car. One of the men said he was a federal officer. They drove Montes for a few blocks before letting him go. He was told he would find his car parked someplace in south El Paso in the next two hours.

For whatever reason, Montes decided to report this theft of illegal, prohibition-era liquor to the police. Montes told police that two Americans and “a man who looked like an Italian” had hijacked him.

The sufficiently Italian looking man Montes later picked out of a line-up was Frank Ardovino, a thirty-four year old chauffeur. Ardovino and taxi driver Robert Pollard were charged with the hijacking along with two deputy constables, John Woods and Jack Litchfield. The deputies claimed they seized the liquor legally with the intent of turning it in to customs authorities.

W. O. Hamilton, an attorney representing both Ardovino and Pollard, said Ardovino was at home in bed at the time of the hijacking.

Ardovino was ultimately released as there was insufficient evidence to connect him to the hijacking. Montes later said he was unsure it was Ardovino with the other men. He couldn’t get a good look; the third man had dark hair, but was in the backseat of the other car and holding a flashlight during the search. Ardovino was set free, but this would not be his last run in with the law.

Frank Ardovino, or Ardovina, depending on the source1, was born in 1898 in Salerno, Italy. He arrived in America by boat, landing in Yonkers, New York at age 12. Seven years later he was a naturalized citizen, enlisted in the U.S. Army, and stationed in El Paso. He fell in love with the desert and decided to one day make it home.

After his Army service, Ardovino found work in El Paso as a taxi and limo driver. A career misstep in 1934 led to a brief respite on McNeil Island, Washington, but he returned to El Paso to follow his passion.2 Ardovino had a taste for the finer things in life; good food, good drinks, and high class entertainment. It all came together at his restaurant, Italian Village. Ardovino advertised fine Italian dining under his personal supervision; plus he boasted something especially important in El Paso at that time: air conditioning. And what goes better with fine dining in a cool atmosphere than a few games of chance? Table games were made available in private rooms in back of the restaurant.

But, as was their habit, the police took an interest in the games. On a Saturday night in June, 1937, Night Chief Butchofsky and his officers raided the establishment. Eight arrests were made, including Ardovino. Police seized elaborate gambling equipment plus $480 in cash. Ardovino was charged with operating a gambling game.

Ardovino could not help but wonder why it was that the ordinances against gambling were so meticulously followed when it came to his establishment while other clubs seemed free to run their games. Something stank.

I Fought the Lawson

After the raid, Ardovino and his attorney, W. O. Hamilton, decided to take the fight to City Hall. Hamilton demanded jury trials for Ardovino and the others arrested. He promised startling revelations on the gambling situation in El Paso and started subpoenaing witnesses, including Night Chief Butchofsky. Hamilton claimed he had a witness who could testify to money changing hands between gamblers and city officials. According to Hamilton, Dave Lawson held his monopoly on gambling through official sanction.

“I’m not in the gambling business,” Lawson responded. “I have been trying, without much success, to make a living out of a bowling alley and a bar where nothing but beer and wine is sold.”

Hamilton upped the pressure on city officials, threatening to seek the help of Texas Rangers if he didn’t receive “proper” cooperation from local law enforcement in investigating gambling. Hamilton was not to be ignored, he happened to serve as chairman of the City Democratic Committee, which meant he presided over city elections.

Hamilton’s legal bombardment was far from over. Next, he and Ardovino took it directly to the rival gamblers in court, seeking an injunction against Dave Lawson and his former partner, Frank “Ducky” Gowen. The complaint sought to restrain the men from using the Knickerbocker Club and Gowen’s club, the Annex, for the purpose of gambling or exhibiting paraphernalia used in gambling.

The same day, Ardovino and the other defendants quietly pleaded guilty and paid fines collectively totaling $104.

Ardovino’s legal action against the Knickerbocker Club threatened to set off a gambling war, something El Paso Sheriff Christian Petrus Fox was determined to prevent. Sheriff Fox blasted Ardivino’s character in a scathing statement.

“This department feels that it is its unalterable duty to see that there is not a recurrence of the present ‘two-bit’ gambling scandal that has been created by an ex-convict who, not so long ago, finished serving a sentence in the Federal Penitentiary at McNeil Island on a narcotic charge,” Sheriff Fox declared. “We have a happy community, one in which decent people should be able to live in contentment and confidence.”

Sheriff Fox went on to threaten arrests to halt a gambling war, promising to “wear out the County Jail” with gamblers.

Hamilton fired back, accusing Sheriff Fox of being well aware that open gambling was going on in El Paso and doing nothing about it.

“If the Sheriff had been in a positon to enforce state laws, there would be no suit for an injunction against gambling joints in Forty-first District Court today,” Hamilton said, then proceeded to call the Sheriff’s statement “Old Man Bull.”

“He talks of wearing his jail out with ex-convicts and their associates who create gambling scandals,” Hamilton said. “Then let him raid the Knickerbocker Club, The Annex, and the Plaza Club and throw those he catches in jail. He can wear it out in record time if really wants to.”

Ardovino and Hamilton weren’t the only El Pasoans to notice the seemingly selective enforcement of gambling laws. The Herald-Post had long been incredulous toward the city’s efforts to curb gambling, now its readers were chiming in. A letter to the editor from an H. W. Loggins suggested class and even racial considerations were at play.

“Some people are curious to know why,” Loggings wrote, “in the recent raids, the Knickerbocker and the Annex, and some other of the uptown gambling houses, when the raiding parties appeared, only had some innocent non-gambling game in progress; but when they raided the Negro gambling house they found blackjack or some other gambling game, and arrested them.”

Dave Lawson had his defenders in the paper as well. A Mrs. Marcus W. Russ wrote in to defend Lawson while taking some not-so-subtle jabs at hypocrites in the community.

“He is a man refined in manner,” Russ wrote, “gentle and courteous and his money has never been so ‘hot’ that all the charities and so-called charities have ever found it expedient to drop any of the ‘hot’ money once they grasped it.” She went on to say, “If Jesus came to El Paso, I like to think he would visit Dave Lawson and maybe dine with him.”

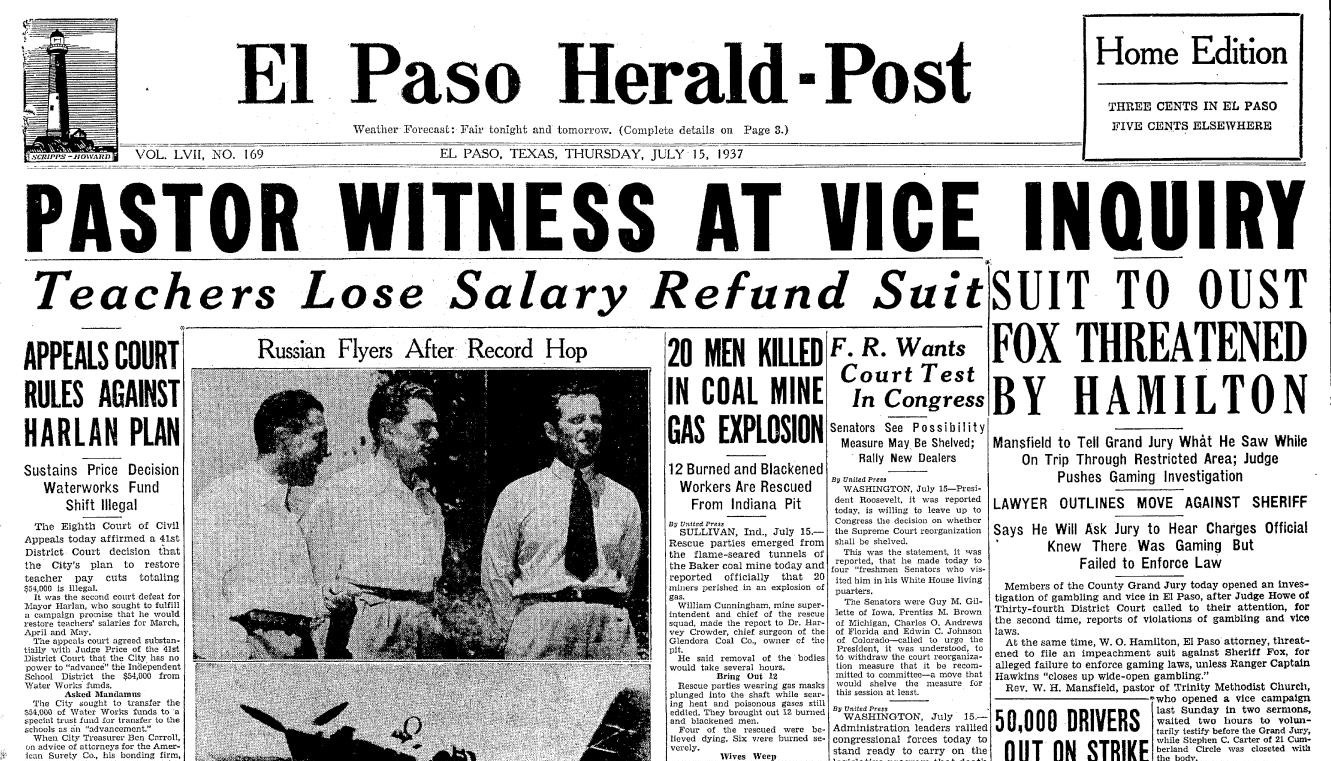

The public dispute had an all too familiar result. Judge Howe of the Thirty-fourth District Court convened yet another grand jury to investigate gambling and vice in El Paso. The Mayor was different, the Judge was different, and there was even a different firebrand reverend on the stand; but the outcome would not be a surprise.

Meanwhile, Hamilton continued his legal advance. The injunction against Lawson and the Knickerbocker was granted after Ardovino put up a $500 insurance bond to see it through. The court denied Lawson a bond to halt the injunction. “Ducky” Gowen caught a break; he and The Annex were found to be improperly attached to the suit and were removed. But Hamilton promised to file more suits for injunctions against all the gamblers in town. It was mutually assured destruction. If Frank Ardovino was getting shut down, they were all getting shut down.

“We will take on anyone who is operating gambling in El Paso,” Hamilton said. “This is just the beginning.”

Hamilton’s next maneuver was to threaten Sheriff Fox with an impeachment lawsuit for his failure to enforce gaming laws. Under a seldom utilized state law, certain county officials, including the sheriff, could be removed from office through a trial by jury following a petition filed in district court. Hamilton pledged to file the suit unless Texas Rangers closed up gambling in the city.

As luck would have it, Captain “Red” Hawkins, commander of Texas Rangers stationed at San Angelo, just happened to have arrived in town that week.

“It’s just a routine visit - nothing unusual,” Hawkins said. Ranger Hawkins met with City and County officials and decided he was satisfied with their ability to control the gambling situation. “There is no reason for any Rangers being sent to El Paso and we received no such order from the State Department,” he said.

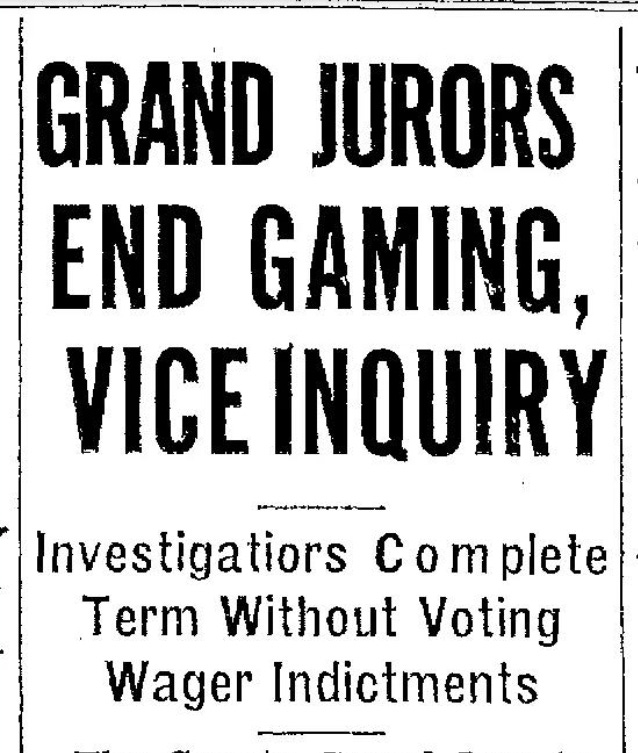

The grand jury seemed satisfied as well, they declined to return any gambling indictments. The grand jury’s inaction killed the momentum of Hamilton’s impeachment efforts.

“In face of the County Grand Jury adjourning without any action, I won’t know what action I will take in regards to the Sheriff until I have conferred with him on his return,” Hamilton said. Hamilton’s war on the gamblers had fizzled out. A few weeks later, the injunction against Dave Lawson was dismissed.

The Aftermath

The gambling war had come to an end but it wasn’t the end of Dave Lawson and Frank Ardovino’s troubles. Their public feud had put gambling and vice under the microscope. Yet another court of inquiry was called in 1938.

The Knickerbocker Club was raided once more and Dave Lawson was again hauled in on gambling charges. On top of gambling at his club, he was also accused of running a horse racing wire service out of a New Mexico “mystery house” filled with radio and telegraph equipment for receiving horse race outcomes from across the country and transmitting them to bookies.

Meanwhile, Ardovino closed up the Italian Village, dissolving his business partnership in 1939. He and his wife moved into the Savoy Hotel where he would work as a manager. As part of his duties, it was alleged, he operated a gaming room out of the hotel. In 1941, a sting by the Texas Rangers set out to prove it.

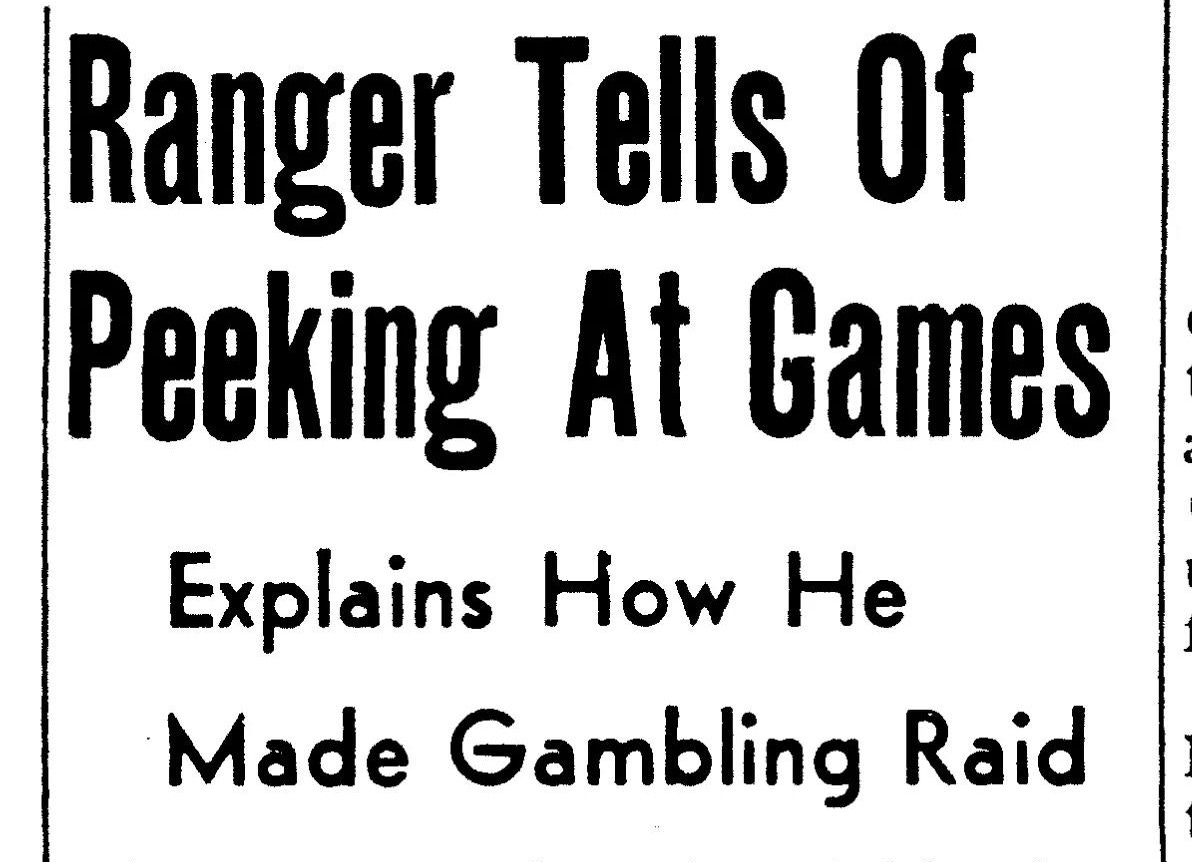

From his stakeout position in the nearby Caples building, Texas Ranger Pete Crawford watched several men play cards and dice games in the Savoy Hotel. Ranger Crawford, aided by El Paso Police, raided the room, confiscating a dice table, several decks of cards, and other equipment.

The magnitude of the raid was disputed at trial. Under cross-examination by defense attorney W. R. Fryer, the Ranger testified he confiscated only a dollar from the dice table and $40 from the pockets of one card player.

“In this gambling emporium they had netted only a dollar at the dice table, then,” Fryer scoffed.

The defense also questioned the legality of the search. Ranger Crawford admitted he did not have a search warrant and could not give an answer as to why he had not tried to get one.

Nevertheless, Ardovino was convicted on felony charges of maintaining a gambling establishment and sentenced to two years in prison. It was El Paso’s first successful felony conviction in a gambling case in 10 years. The victory would be short lived.

Ardovino’s attorney appealed to the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals, challenging the sufficiency of the evidence. To prove Ardovino was keeping a gambling room, the State had relied solely on the fact that Mr. L. Hershey, a player who had rented the room and claimed to own the gambling paraphernalia, had looked to Ardovino for advice before agreeing to allow authorities to destroy the paraphernalia. The Court determined in Ardovina v. State3 that the State’s case was not strong enough to overcome the presumption of innocence. The conviction was reversed.

The Land of Enchantment

If Dave Lawson and the Texas Rangers wanted El Paso, they could have it. Frank Ardovino was done getting the high-hat in Texas. He took his talents across the stateline into New Mexico, setting up shop in the El Paso suburb of Anapra, today’s Sunland Park.

In New Mexico, Ardovino would find a more welcoming community and a local government appreciative of entrepreneurs such as he. In 1947, Ardovino, along with other investors including his nephews Salvador and Antonio, opened the Valley Country Club as a private club. Their “club” liquor license exempted them from the fees paid by public bars and allowed them to lock their doors to non-members. Private club status made them virtually immune to police raids, as did their clientele, which included several public officials. It was now Frank Ardovino’s turn to watch his competition get raided while his games went on.

Ardovino’s newfound influence was on full display in December 1948 when W. L. Hill, an ambitious Las Cruces constable, attempted a raid on the Valley Country Club. Constable Hill and two deputies raided the club early one Sunday evening, before customers had arrived. They seized three roulette tables, 15 slot machines, three blackjack tables, and the tops of three dice tables.

Constable Hill had his men load the seized equipment into his trailer then attempted to arrest Ardovino. But a big man with sideburns, known only as Bob, intervened. Bob started shouting, ordering other men to take the constable’s gun. Constable Hill told Bob he was under arrest but Bob ignored him. Instead, Bob retrieved a roll of bills from Ardovino and tried to pay off the lawman.

“I said this was one time there wouldn’t be a fix,” Constable Hill said. “But I made the mistake of letting Bob go to a telephone.”

Bob called a higher authority, Justice of the Peace T. V. Garcia. The Justice quickly arrived and tried to convince the constable to return the gambling equipment. Then, Justice Garcia’s armed officers appeared, along with a dozen “tough looking men” from the club. Garcia told one of his officers to take Constable Hill’s gun. When Hill refused, Garcia had him arrested. Hill relented, certain there would be shooting if he resisted.

“Garcia didn’t say what I was arrested for,” Constable Hill said. “It was some trumped-up charge. While I was detained Ardovino broke the hasp on my trailer. Some of the men were tipped to carry the gambling equipment back to the club.”

“Hill is a damn liar,” Justice Garcia said when told of Constable Hill’s story. “He is a Republican trying to make a lot of noise. It’s politics. I’m not a friend of the gamblers. Did Hill tell you about the man he tried to hit at the bar?”

District Attorney Bill Scoggin of Dona Ana County was unmoved by Constable Hill’s attempted heroics. According to the DA, Hill wasn’t properly qualified to have conducted the raid.

“You can’t do anything against the Valley Country Club in New Mexico,” Constable Hill conceded.

For his part, Ardovino denied any knowledge of a raid, none of his equipment had gone missing. It was business as usual at the Valley Country Club. But just as Ardovino was establishing himself as the new boss fixer, a horrifying discovery in the New Mexico desert would bring it all to a tragic end.

Next time on Borderland Vice: Dave Lawson builds his bowling legacy; Frank Ardovino tries to protect his gains; and an unsolved murder shakes the gambling world to its core. In our thrilling conclusion, we learn the tragic tale of Cricket Coogler.

Frank Ardovino appears in most sources as Ardovino up until 1934 when many sources, including advertisements for his restaurant, show him as Ardovina. In at least one article he is referred to as both. By 1948, most sources use only Ardovino.

Editor’s note: This publication makes no value judgement on the activities described in this piece and would never discourage patronage of any of the fine dining establishments that bear the Ardovino family name. Management is of the opinion that Desert Crossing is an American treasure and you should check it out.

Ardovina v. State, 143 Tex.Crim. 43, 156 S.W.2d 983 (1941)

![Or Give Me Death Industries [substack edition]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!rF5C!,w_80,h_80,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep,g_auto/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F6790ca65-d171-497c-85d0-70c43dab81be_736x736.png)

![Or Give Me Death Industries [substack edition]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!C8FR!,e_trim:10:white/e_trim:10:transparent/h_72,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F918e6633-25ca-4b95-b28f-d4d1bfeccce8_1344x256.png)

Can’t wait to find out who Cricket Coogler is!